Elizabeth West and Peter Darrell co-founded Western Theatre Ballet in 1957. They aimed to find new audiences for ballet, performing in theatres that large companies did not visit. It was their ambition to commission ballets reflecting the spirit of the day and, crucially, to revitalise ballet’s theatrical dimension (hence the word ‘theatre’ in the company’s name). Lord Harewood’s invitation to perform at the Edinburgh Festival in 1961 was an important recognition of what Western Theatre Ballet had achieved. The programme they chose was daunting for a small company: Kenneth MacMillan’s version of Brecht/Weill’s Seven Deadly Sins, along with Salade choreographed by Peter Darrell and Le Renard choreographed by Alfred Rodrigues. A particular strength of the evening was the designs, which for all three ballets were overseen by Barry Kay. Ian Spurling was MacMillan’s designer, his set constructed, rather than consisting of painted cloths and flats, the seven locales of Anna’s sins announced on large lettered cubes moved around the stage by the cast.

The Seven Deadly Sins, which Berthold Brecht and Kurt Weill wrote after they fled Nazi Germany (it was their final collaboration), is an excoriating assault on capitalist morality. It was conceived as a satirical ballet chanté and first commissioned by Boris Kochno and George Balanchine in 1933. The work had been largely forgotten until Balanchine revived it in 1958.

Its heroine, Anna is a split personality, presented in MacMillan’s ballet as two sisters. The singing Anna is all rational calculation. Her counterpart, the dancing Anna, is instinctive, natural, unguarded and generous. Anna is despatched into the world to ‘make good’. The deadly sins from which her sister has to save her are the instincts that stand in the way of success. The two sisters, really one, journey around the America of Brecht’s imagination encountering a different sin in each city. Each humane impulse of the dancing Anna (Anya Linden) is stigmatised as a deadly sin by the singing Anna’s voice of reason (Cleo Laine). Virtue subsists only in acquiring money, symbolised by the home in Louisiana to which they eventually return.

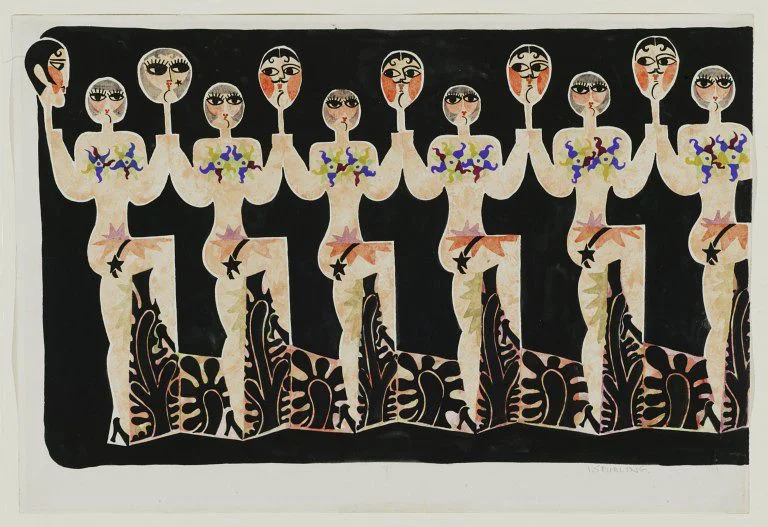

©Ian Spurling Costume design for Corps de Ballet of Seven Deadly Sins 1961

Lotte Lenya was to have been MacMillan’s Singing Anna, as she had been both in the 1933 and in the 1958 revivals. She had not understood that the choreography would be new and withdrew from the production to be replaced by Cleo Laine. For The Times the ballet made the strongest impression of the evening. “Whether or not we agree with Brecht”, the review (unsigned) continued, “that there is anything specifically bourgeois about this immorality, the piece should make us profoundly uncomfortable. That it did not tonight was partly due to Mr Kenneth MacMillan’s and Mr Ian Spurling’s all too brilliant evocation of the world of Pabst’s films, which now seem safely quaint, and partly to the invincible warmth of Miss Cleo Laine’s singing. The final horror should lie in the fact that Anna I thinks of herself not as hard-bitten but as a pillar of morality: no room here for a heart of gold, or even a heart at all.

A music critic, Peter Heyworth reviewed the premiere for The Observer. “What was conceived in rage is swaddled in pity and savage satire is reduced to piquant paradox.” However, Andrew Porter of The Financial Times came to MacMillan’s defence. “It is not The Seven Deadly Sins, one feels, that Brecht and Weill intended. On its own terms, however, if not on theirs, MacMillan’s choreography is filled with brilliance and invention and the whole presentation, in Ian Spurling’s extremely clever set, is exciting.”

- 1961

- Western Theatre Ballet, Edinburgh Festival

- Music Kurt Weill

- Design Ian Spurling

- Cast Anya Linden, Cleo Laine