Noctambules was of a different scale to MacMillan’s previous ballets. It was his first work for the main company on the Covent Garden stage and his first to a commissioned score.

In MacMillan’s scenario, a vengeful hypnotist hypnotises the audience in a small theatre after they scoff at his act. Under hypnosis a soldier becomes a hero, a couple fall in love, a faded beauty regains her charms and wins four suitors. The hypnotist, discards his stage assistant for the beauty he has created, but she, waking from her dream, recoils from him. At the premiere, Leslie Edwards was the hypnotist with Nadia Nerina as the Faded Beauty, Desmond Doyle as the Rich Man, Anya Linden as the Poor Girl, Brian Shaw as the Soldier and Maryon Lane as the Hypnotist’s Assistant.

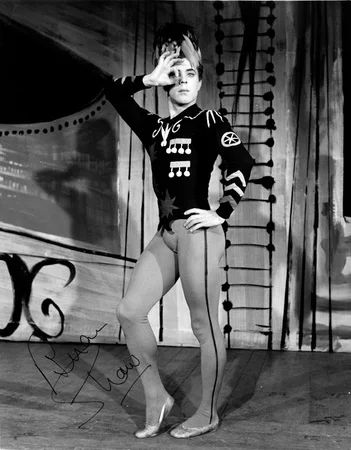

Noctambules (1956). Photo: Michael Dunne. Photo supplied courtesy of the Music Library, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

For Mary Clarke, writing in Ballet Annual, “there was never a trace of the tiro in a work that was completely consistent”, but the scenario fell short with a sense that “strange happenings under hypnosis weren’t strange enough.” Alexander Bland of The Observer thought the ballet fell short – and for this he blamed Georgiadis’s designs. “He has attempted, fatally, to combine mystery and drama with a kind of feverish gaiety. How can one take seriously a pantomime Svengali in black, green and lilac; or a rich lover whose velvet is sprinkled with drop pendants: or a soldier who mows down his friends in a crazy tommy-gun dream – but decked in purple cock’s plumes? This is not drama but melodrama – Grand Guignol at the Chelsea Arts Ball. All the same a real imagination is cooking away there somewhere. When the fitful fever has died down, MacMillan may well produce something to astonish us.”

But Clive Barnes, writing for Dance and Dancers, was contemptuous of older critics’ dismissal of Noctambules as ‘melodramatic’. “The choreography, which owes something possibly to MacMillan’s very first ballet Somnambulism, is often shockingly original. It has something of Ashton in it (the pas de deux and grand adagio, for example, have certain Ashtonian characteristics) but MacMillan’s style is remarkably individual. He is to Ashton what Robbins is to Balanchine; two formidable and self-willed apprentices for two formidable and self-willed sorcerers.”

The Manchester Guardian’s critic JHM (possibly James Monahan) praised “an extremely good work, rich in well-made dances.” But for The Times’ un-named critic, “every effect did not tell perfectly in the first performance: what pleased the audience was a ballet with aspirations but not pretentiousness and a ballet that effectively brings out the qualities of some of the younger dancers in the company.” A group from Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, in London to discuss possible exchange visits between the two companies, was, The Times reported a few days later, “enthusiastic about Noctambules, whose choreography, decor, and music lie far outside the experience of the Bolshoi repertoire”

This was also the first time MacMillan had choreographed to an original score, not a completely happy experience. De Valois had suggested Humphrey Searle, to whom MacMillan gave a very detailed scenario. When the piano score arrived, it was patently too long, but the young MacMillan was too diffident to ask for cuts. Mary Clarke remarked that it was “admirable in suggesting the atmosphere, but less successful in developing the narrative.” For The Manchester Guardian’s JHM the score seemed “altogether too apocalyptic: the drumming and discordancies belong not to a charlatan’s theatrical mystifications but to the day of judgement.”

First Performed: 1 March 1956

Company: Sadler's Wells Ballet

Music: Humphrey Searle

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast: Leslie Edwards, Maryon Lane, Nadia Nerina