Sir Kenneth MacMillan, principal choreographer of the Royal Ballet, has been controversial ever since he staged his first professional ballet at Sadler's Wells Theatre as a young dancer in 1955.

He has since become one of the most important forces in the dance of our time. He represents the second generation of creativity at the Royal Ballet, after the founding figures, Dame Ninette de Valois and Sir Frederick Ashton; like them he was director of the Royal Ballet, from 1970 to 1977.

His beliefs about the potential of dance to explore the human condition, his determination that his work must reflect not the fantasies of nineteenth century swan-upping but the emotional crises known to men and women today, have sometimes made audiences uneasy. Ironically, his full-length ballets Romeo and Juliet; Manon; Mayerling, are among Covent Garden's greatest draws and have achieved the status of repertory classics, while his short works are eagerly acquired by companies worldwide. He remains, as always, a very private man whose chief concern is still with finding new possibilities for movement.

“I wanted to make ballets in which an audience would become caught up with the fate of the characters I showed them”

“I never sat down and thought about what ballet should do in the theatre, but early in my career I knew that what I wanted to put on stage had to have more reality than much of what I was seeing in the 1940s and 1950s. That might seem strange when one considers what an artificial medium ballet is, with its women on pointe and its formal language - the whole aesthetic of ballet is not about reality - but I was at odds with everyone who wanted ballet to continue to be 'traditional'. 'I was influenced by other aspects of the theatre and I recall an article by John Osborne - whom I admired very much - in which he spoke of ballet as being effete. Little of what I was seeing then had any contact with a real world of feeling and human behaviour. Ballet looked like window-dressing. I wanted to make ballets in which an audience would become caught up with the fate of the characters I showed them. The only way to get the sort of expressivity I aimed for was to know how the characters felt and find a means of showing that.”

“I wanted dance to express something largely outside its experience. I had to find a way to stretch the language - otherwise I should just produce sterile academic dance. Even so, the language had to remain very precise. In some of the work I have done which I like best, the movement came swiftly - in the solo I recently made for Anthony Dowell as the tragic, ineffectual husband in Winter Dreams, and in the ‘grief’ duet in Isadora when Duncan and Paris Singer hear of the death of Isadora's children.”

This is one of the rawest and most heart-tearing pieces of choreography that MacMillan has made. In it he pushed dance to serve feelings that only one choreographer - Antony Tudor - had shown before.

“It is very English - you mustn't show emotion, and I think my ballets embarrass people because I let emotion out.”

“The big difference between Tudor and me is that he always sought to conceal emotion, while I want to get it all out in movement. Tudor's heroines agonise desperately inside and try not to reveal their suffering. It is very English - you mustn't show emotion, and I think my ballets embarrass people because I let emotion out.”

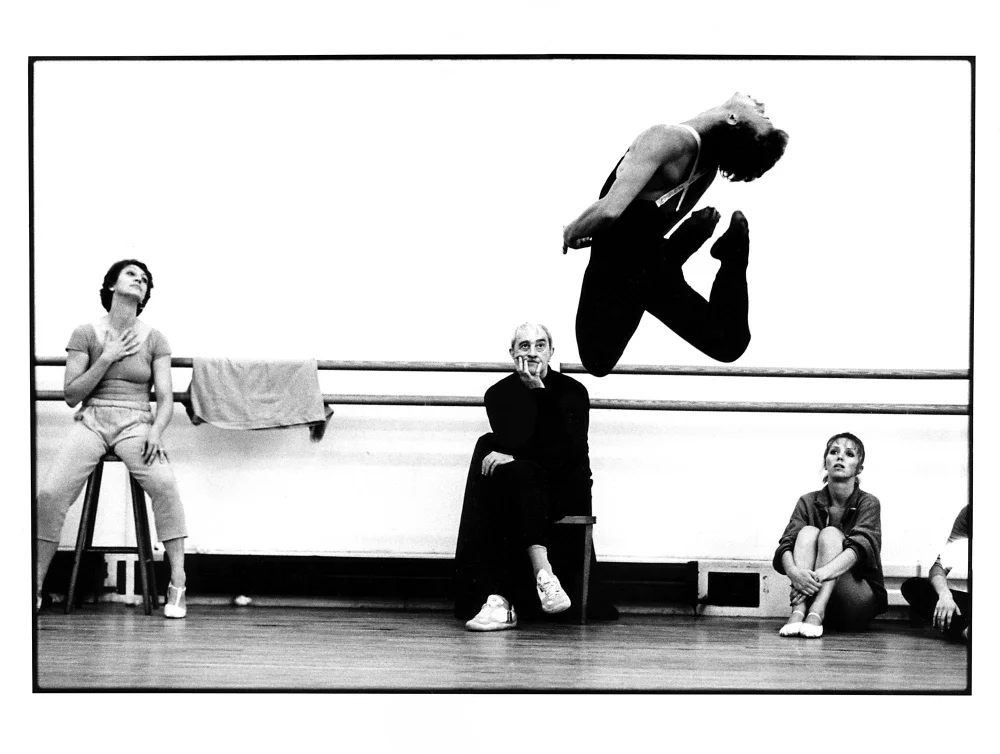

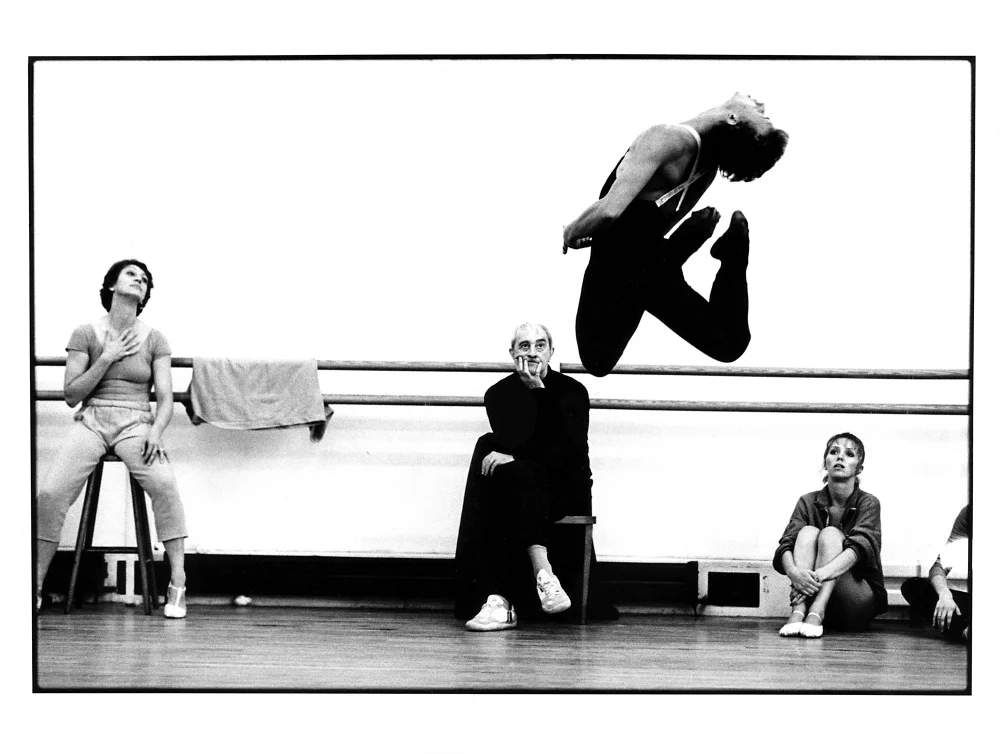

©ROH Archives / Neil Libbert Kenneth Macmillan, Monica Mason, Fiona Chadwick and Simon Rice rehearsing Rite of Spring.

“My childhood was very emotionally upsetting. My emotions were stored away and the idea of releasing them, of finding ways of exploring other people's emotions, came out in my work. I chose a strange medium in which to reveal feelings. But since I didn't have a good academic education, I couldn't become a writer. When I saw Look Back in Anger, it was a great eye-opener and an influence, because John Osborne had found a way to express his emotions and his frustrations. This was important to me. Emotion could be released, and though it took a longer time for me to achieve this in dance - the language is more intractable, I suppose - it gave me a vital inspiration.”

Was there implicit in all this a conflict with an establishment? “I think my entire career has been a fight against the Establishment and its view of ballet. I feel that I had a lot of trouble with the Opera House establishment because of an almost pre-war view there of what ballet was about.” A prime example came in 1965 when Covent Garden would not allow MacMillan to stage Mahler's Song of the Earth . It was MacMillan's friend John Cranko who offered him the chance to mount the ballet in Stuttgart. And when it was recognised as an important work, the Royal Ballet duly acquired it. MacMillan has not made concessions: audiences have had to accept his view of things.

“Audiences are upset, not always by the subject matter, but by the way I treat it”

“But even so, my ballets can still offend the public. Valley of Shadows, which showed a concentration camp, did not get many performances. It cut across people's strong received ideas about what dance should do. Audiences are upset, not always by the subject matter, but by the way I treat it.” And yet they would not be offended if such matters were shown by a modern company? “It is like trying to preach to people who can only believe in what they think ballet should be. Prejudice is hard to break down.” When MacMillan staged his full-length ballet about Isadora Duncan, Earth-Mother of modern dance, it was as if he had lost patience with an ultra-traditional view of ballet, and had broken the mirrors on the dance studio wall that reflect the dancers' sweating and self-obsessed bodies so as to show the world of theatre outside.

“I don't think that I consciously set out to do that, but when I look back it does seem as if I were impatient with ballet. Perceptions had to be broadened. Isadora was a very 'theatrical' piece in that I used things the audience didn't expect: speech; the splitting of the role of Isadora between a dancer and an actress. If you work in the theatre, you have to be a magician, and as well as illuminating your subject, you have to excite and mystify and make the audience wonder.' Nowadays MacMillan's big-scale ballets are staples of the repertory. Has the fighter against the crusted and the reactionary become a Grand Old Man? “It's strange, but latterly I have felt that I am more accepted by the public. Of course, there's a danger in the immense popularity of the three-act ballet. Increasingly audiences want to see full-length works, and turn away from triple bills. The curious thing is that only here in Britain and in Russia is there that tradition of extended creativity, of choreographers making evening-long ballet. I'm a product of that system and I love making big works. Since my illness (a heart attack three years ago) I find it difficult to maintain my stamina to create a full-evening ballet, though I still believe in them.”

About ballet-making, he is frank. . “A creative artist is driven by his gifts. Now that I am married and have a grown-up daughter, things are different. But as a young man I never thought of anything except the ballet I was creating or the next ballet I had to do. The tension was horrible, yet I had to get it out of my system each time. Now, working in an Opera House with a large company, I have to produce big works that will keep the company dancing. But there are moments when I feel I need to make a small-scale piece, which is difficult within the context of the Opera House.”

“Although I'd thought about making a ballet from Three Sisters , I wasn't aware, when I made the original pas de deux for Darcey Bussell and Irek Mukhamedov, of what I had created. When I saw it, I realised that this was the farewell between Masha and Vershinin from Three Sisters , and I had to go on and make Winter Dreams. 'The subconscious is strange in my ballet-making: as I watched one section of Winter Dreams, I found myself becoming nervous because I did not understand if what I had created was right. I was surprised by what I saw. The subconscious takes over, and it is never really satisfied. It acts as a censor, and I become my own critic about the form of what I am making. It is very mysterious. I also realise now that I am no better and no worse than the music I use. This may sound patronising to my composers, but it is true. My regret with my last full-length ballet, The Prince of the Pagodas, is that the Britten estate would not sanction any cuts. With sensitive editing - and the trustees ought to realise that I would not desecrate a major score - I could have made a tauter ballet. 'But I have to do what I have to do, and I hope the public will like it. If I ever stopped to consider what people wanted, or what I thought they'd like, I'd never do a thing.”

Clement Crisp is dance critic of The Financial Times. Hear him describe what first drew him to MacMillan's work in an interview with Brendan McCarthy, available in the audio gallery.