Kenneth MacMillan was the leading ballet choreographer of his generation. Born of a poor Scottish family, he had a burning sense that ballet theatre should reflect contemporary realities and the complicated truths of people’s lives. He became director of The Royal Ballet and created some of the outstanding dance works of the twentieth century.

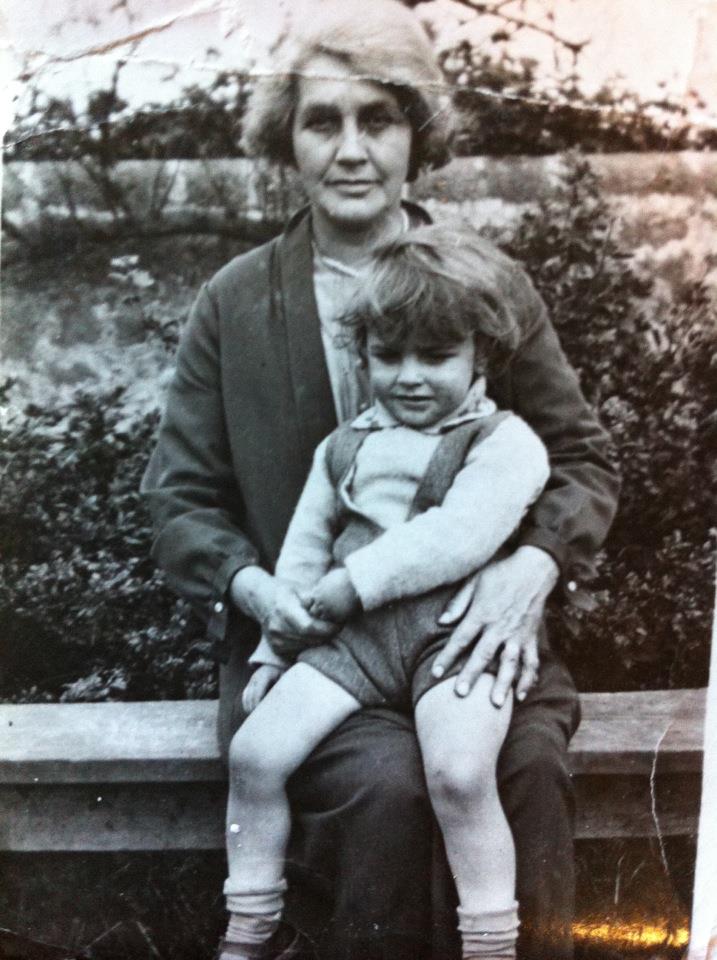

Edith Shreeve MacMillan and Kenneth MacMillan circa 1932

He was born in Dunfermline, Fife on 11 December 1929. His parents, William and Edith MacMillan, had met in Norfolk where William was briefly stationed, en route to France, during the First World War. After William, a coal miner, was gassed in the conflict, mining was no longer possible for him. Instead, he tried and failed as a chicken farmer. The family fled the farm in the middle of the night (“a moonlight flit”) and went south to Norfolk, to live in Great Yarmouth, where William could only find occasional work during the Depression years of the 1930s.

When Kenneth was 11, he won a scholarship to the local grammar school. The Second World War had begun and Great Yarmouth was repeatedly bombed by the Luftwaffe. The school was evacuated to Retford in Nottinghamshire and it was here that he first discovered ballet. He had already learnt tap and Scottish country dancing and taken part in entertainments for soldiers at American air force bases. In Retford, he took tap lessons from Jean Thomas, a local dance teacher, who encouraged him to try ballet. He was soon obsessed and devouring back issues of The Dancing Times in the local library.

Edith MacMillan, who suffered from chronic epilepsy, died in 1942. Kenneth was emotionally devastated. ''I remember coming back for my first school holiday to Yarmouth, and was met at the station by my father and my sister, who told me my mother had died the previous night. From that moment on, I felt that I was on my own. I wasn't very close to my father. We got on all right, but he was a rather strict Scottish gentleman, rather remote and unemotional, especially to me.”

“A lasting memory of mine was watching Kenneth doing grand jetés across Yarmouth Market Place on his way home from school.” wendy adams

A dance teacher in Great Yarmouth, Phyllis Adams, became, in effect his surrogate mother. She taught him for free and, in effect, shaped his ambitions. “She treated me as an adult, which was wonderful”, MacMillan said in a 1991 interview. “I didn't know what I was going to do when I grew up until I met Phyllis Adams.” Adams realised that she had a prodigiously talented pupil and MacMillan created his first choreography on Adams’ daughter, Wendy and a friend. It was, she remembers “a duet with chairs to I love a Piano ”. “A lasting memory of mine”, she continued, was “watching Kenneth doing grand jetés across Yarmouth Market Place on his way home from school.”

When he was 15 he found an advertisement in The Dancing Times offering scholarships for boys at the Sadler's Wells Ballet School. He wrote to Ninette de Valois in the name of his father. The letter got him the audition, but did not fool anyone, as he discovered years later when he took over as director of the Royal Ballet and found his file in the archives. The audition was participation in a class with the Sadler's Wells Company. ''I was put between Margot Fonteyn and Beryl Grey and I was terrified, added to which I was screamed at, quite rightly, by Miss de Valois for being late for her class.''

Ninette de Valois was persuaded of his ability and awarded him a scholarship consisting of free tuition, an accommodation allowance and five shillings a week pocket money. At the end of term, MacMillan told his headmaster at the grammar school that he would be leaving, who in turn proudly announced the news at morning assembly. ''I was mortified,'' MacMillan recalls. ''I fled the school that morning and never went back.''

In many of MacMillan's ballets the hero or heroine is an outsider. ''Well, I felt like an outsider as a child and it all started with the moonlight flit. I had to keep that secret. Then, when my mother was ill and having fits, I was told never to talk about that. And, of course, in a place like Yarmouth, I had to keep my dancing a secret, because they would have thought it was appalling. There wasn't one other boy in either of my dancing schools before I came to London. It all made me feel very out of it, and this creates in a person a kind of schizoid state.”

“It was the first time I was with people whom I could talk to about the things I really felt.” Kenneth MacMillan

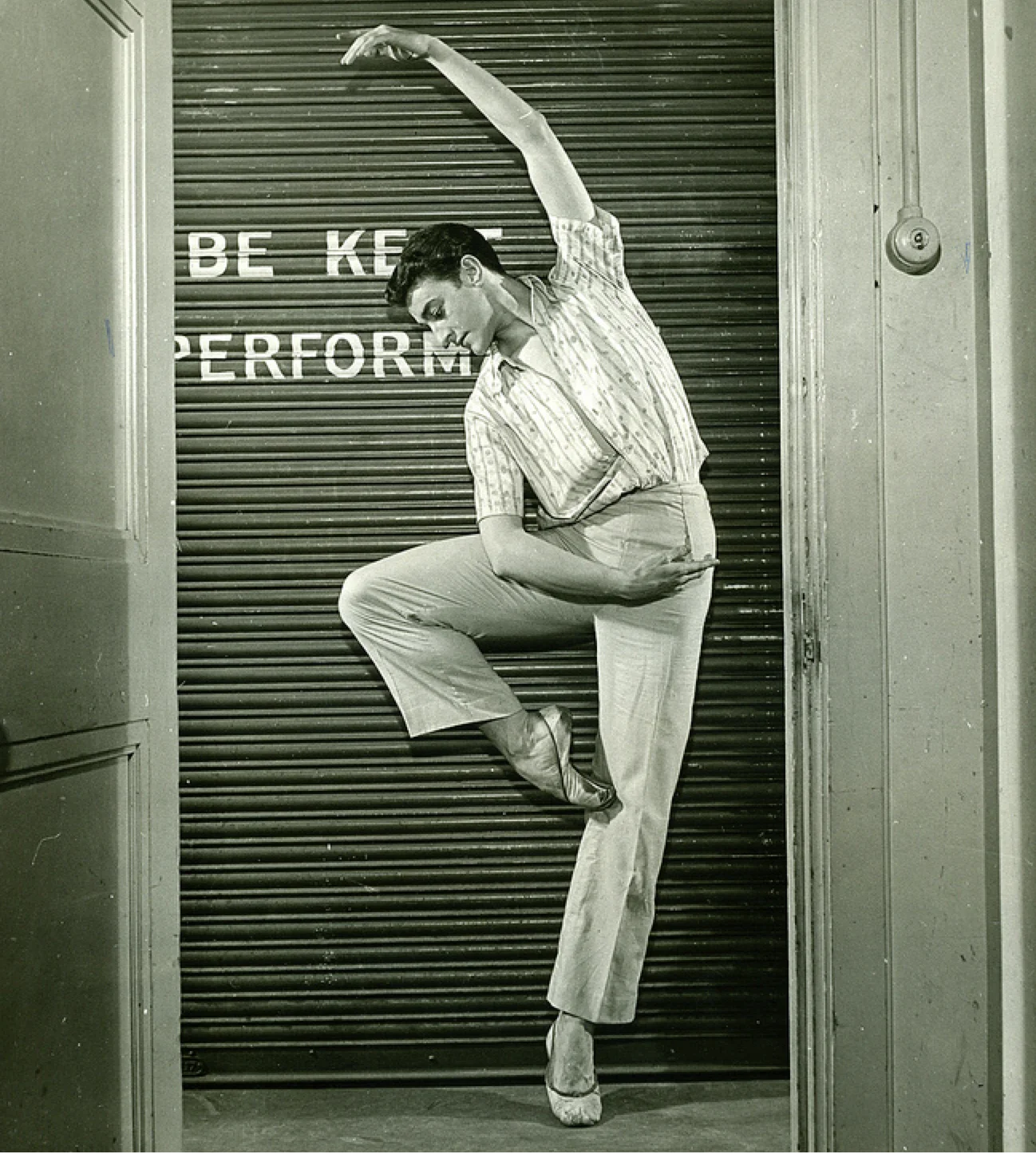

Kenneth MacMillan 1951 ©Roger Wood / ROH Archives

At the Sadler’s Wells School MacMillan began to meet kindred spirits his own age. “It was the first time I was with people whom I could talk to about the things I really felt.”

In little over a year he was a member of the Sadler's Wells Opera Ballet (later Theatre Ballet). Soon he moved to the larger Sadler's Wells company, now based at Covent Garden. And he went on its first American tour, dancing the role of Florestan in the last act pas de trois in The Sleeping Beauty on the company's triumphant opening night in New York in 1949.

His elegant classical style attracted admiration. The dance writer, Peter Brinson, remembered “ a tall, obviously talented dancer with a terrific jump”, who was notable also as a convincing Sherlock Holmes in Margaret Dale's The Great Detective, and moving actor-dancer in John Cranko's The Lady and the Fool.

But MacMillan was increasingly troubled by stage fright and this was an important reason why he turned his hand to choreography. Somnambulism, his first workshop piece for a Sunday workshop under the direction of David Poole, showed evident flair. This sureness of touch was confirmed by Laiderette in the following year. But it was Danses Concertantes in 1955 that established him. In Clement Crisp’s words, “ Danses was a declaration of talent, of the arrival of the new heir.”

The following years were intensely productive; Noctambules, a commission for the senior company at Covent Garden; an entire evening of his ballets, including House of Birds and Solitaire for the touring company; two works, Winter's Eve and Journey for American Ballet Theatre’s dramatic ballerina, Nora Kaye. But two ballets from this period were highly resonant of their times; The Burrow with its heavy evocation of oppressive enclosure, spoke eloquently to the post-war generation and reminded many of The Diaries of Anne Frank . The Invitation pushed ballet’s theatricality to new limits with its graphic depiction of a rape. Lynn Seymour, on whom he created both works, became the outstanding of his muses and would continue to be so for another twenty years.

“I wanted dance to express something largely outside its experience”, MacMillan explained. “I had to find a way to stretch the language - otherwise I should just produce sterile academic dance.” He was particularly influenced by the abrasive young playwrights of the 1950s, notably John Osborne and Look Back in Anger . Years later he wrote to Osborne saying that the play made him realise that everything in his world “was merely window-dressing.”

In the 1960s MacMillan increasingly proved his mastery of the extended creativity so central to the identity of The Royal Ballet, first with the high theatricality of The Rite of Spring and then in 1965 with his definitive version of the Shakespeare/Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet, the work by which he is best known today to dance audiences around the world.

For several years, MacMillan had ambitions to create a dance setting of Mahler's Song of the Earth . But the board of the Royal Opera House felt that the score was sacrosanct. MacMillan's contemporary and friend, John Cranko, the director of the Stuttgart Ballet, welcomed the opportunity to stage it. It was quickly recognised as one of MacMillan's most intense and beautiful ballets. In a radio interview before he died MacMillan said it was his favourite among his works. Throughout his career, Stuttgart provided MacMillan with artistic refuge, in 1976 it staged the intensely felt Requiem (to the Fauré score), another MacMillan ballet denied performance at Covent Garden - and for similar reasons to Song of the Earth .

In 1966 Kenneth MacMillan moved to West Berlin to become director of the ballet at the Deutsche Oper and remained there for four years. It was a testing time which took a heavy toll of his health. Nonetheless he staged handsome versions of The Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake. Of his own creations in Berlin, the multi-media Anastasia about a mental patient who claimed to be the sole survivor of the Russian Imperial family was an important marker for later works such as Isadora and Mayerling.

In 1970 he returned to London to direct The Royal Ballet. Many in the London’s dance world were resentful at what they regarded as the premature retirement of MacMillan’s predecessor, Frederick Ashton. Almost immediately MacMillan faced a financial crisis and was forced to lose some forty dancers from the strength of the two companies. Temperamentally MacMillan struggled with the demands of administration. Nonetheless in his time as director he greatly expanded the company’s repertory, doubling the number of Balanchine works, introducing ballets by Tetley, Cranko, Van Manen, and Neumeier. Outstandingly, he persuaded Jerome Robbins to come to London to stage Dances at a Gathering .

“In his concentration on long ballets MacMillan was exceptional: no twentieth century choreographer has produced so many full-length works.”

Throughout, MacMillan continued to be busy in the studio making one act works; Triad, Elite Syncopations, Rituals. In 1974 he created the three-act Manon, which became a repertory classic. In his concentration on long ballets MacMillan was exceptional: no twentieth century choreographers has produced so many full-length works - and on subjects which to some minds seemed alien to ballet. MacMillan was deeply wounded by some critical reactions to his three-act Anastasia (an expansion of the work he had earlier staged in Berlin) from writers who thought it a misjudgement of ballet’s range.

Deborah Williams and Kenneth MacMillan on their wedding day 1974

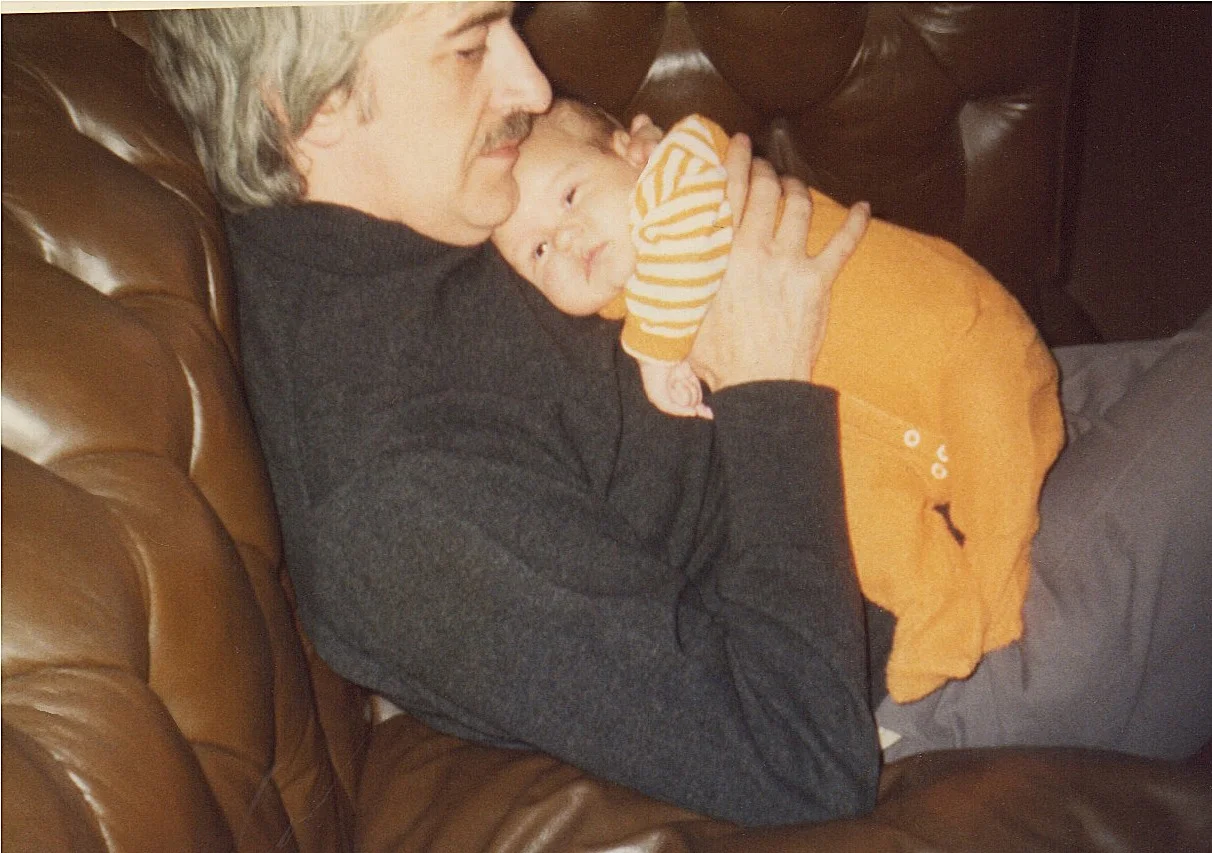

1974 was also the year in which MacMillan married Deborah Williams, an artist who is Australian and together the couple had a daughter, Charlotte. His marriage gave him a new emotional security and helped steel his resilience.

Kenneth MacMillan with his daughter Charlotte 1973

After seven years as director of The Royal Ballet, he retired so that he could focus exclusively on his choreography, a decision triumphantly vindicated by Mayerling, which he made in 1978. Choreographically the richest of his three act ballets, it is a dark study in psychosis. Later works drew on a similarly dark palette; a disturbed family in My Brother my Sisters; fractious mental patients in Playground; Valley of Shadows included scenes in a Nazi concentration camp. Different Drummer told the story of George Büchner's Woyzeck, another example of man's inhumanity to man. And with the full-length Isadora, he sought to breach the barrier between ballet theatre and the theatre of the spoken word.

Kenneth MacMillan was knighted in 1983 and. In 1984, while remaining chief choreographer of the Royal Ballet, he became associate director of the American Ballet Theatre for some five years. For ABT he staged two new works, Wild Boy and Requiem (to Andrew Lloyd Webber's music)., in addition to staging Romeo and Juliet and creating a new production of The Sleeping Beauty.

The final years of his life were immensely productive. After a serious heart attack in 1988 he knew he was living on borrowed time. After a five year period in which he had not created a new work for Covent Garden, he returned in 1989 to make The Prince of the Pagodas , choosing the 20-year-old Darcey Bussell as his young heroine. For Dance Advance, a group of former Royal Ballet soloists, he created Sea of Troubles, a modern-dance version of Hamlet.

In the former Bolshoi principal dancer, Irek Mukhamedov, who joined the Royal Ballet in 1991, MacMillan found his final muse. For Bussell and Mukhamedov, he choreographed a gala pas de deux, which became the core of his ballet Winter Dreams, inspired by Chekhov’s play Three Sisters. The final ballet was replete with cameo roles for older dancers; Gerd Larsen, Anthony Dowell, Derek Rencher.

The Judas Tree, MacMillan’s dark parable of betrayal with Mukhamedov as its brutal anti-hero, was his final ballet. According to Jann Parry writing in The Observer after his death, it was “an intensely personal work, tapping the murkiest streams of his ‘inner landscape’ in a way even he found frightening.”

Kenneth MacMillan died at the Royal Opera House on a night when Birmingham Royal Ballet was presenting his Romeo and Juliet in Birmingham, and when Mayerling was being revived at Covent Garden after a long break. The curtain calls were cut short by the news that he had collapsed backstage. The cast of Mayerling, still caught up in the drama of the ballet were numb with shock. There were gasps and sobs from the members of the audience, who stood in silence before filing out into the night – an astonishingly theatrical echo, Parry recalled, of the funeral scenes that conclude the ballet.

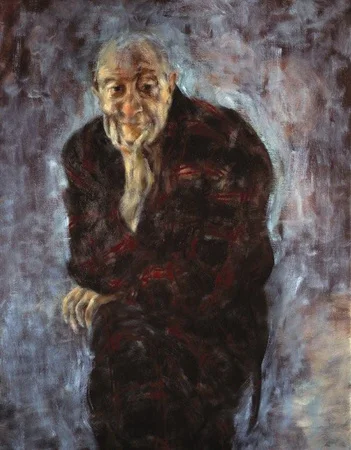

Kenneth MacMillan painting in oils by Deborah MacMillan 1992

Six weeks later The National Theatre’s Carousel, for which MacMillan had choreographed the dances opened on the South Bank. The opening night in the Lyttleton Theatre was an intensely emotional occasion with MacMillan’s family and many of his closest friends in the audience. MacMillan left them a final coup de theatre; as Frank Rich of The New York Times recorded, “in the Act II pas de deux, in which Billy's unhappy teen-age daughter searches for her dead father's love by taking up with a fairground boy, MacMillan joins the hero in seeming to speak to a spellbound audience from beyond the grave.”

Sometimes in his lifetime it seemed as if his gifts were more valued in the wider world of the theatre than in the enclosures of classical dance. Since his death, however, his reputation has continued to grow. Audiences flock to his work, while dancers everywhere vie to perform in his ballets. Throughout his career he kept faith with his classical formation. He married to it a strong theatricality and, underneath it all, a deep moral sensibility. In Kenneth MacMillan’s hands ballet was not a fairytale art, but a powerful mirror to human frailty.