1960 - 1966

1960 - 1966

Le Baiser de la fée

The Invitation

Orpheus

Seven Deadly Sins

Diversions

The Rite of Spring

Dance suite

Symphony

Las Hermanas

Dark Descent

Fantasia in C minor

La Création du Monde

Divertimento

Images of Love

Romeo and Juliet pas de deux

Romeo and Juliet

Song of the Earth (Das Lied von der Erde)

Albertine

Le Baiser de la Fée

1960

Le Baiser de la Fée

1960

“I’m sick to death of fairytales” Kenneth MacMillan once told The Times. Yet Le Baiser de la fée fascinated him and he revisited his 1960 original again in 1986. “It was the music that naturally attracted me”, he told Clive Barnes, “certainly not the story. I realise that the story is not altogether convincing. But I also found the theme, or, if you like, allegory, extraordinarily interesting.”

This was Kenneth MacMillan’s third Stravinsky ballet; the previous two were Danses Concertantes (1955) and Agon (1959). While the score of Baiser had been admired from the time of its composition in 1929, choreographers had struggled to create a completely successful staging. Nijinska’s original for Ida Rubinstein had left Stravinsky cold (“I’m just back from the theatre with a fearful headache as a result of the terrible things I’ve been seeing”). Kenneth MacMillan was the eighth choreographer to tackle Baiser; others who had previously hazarded its pitfalls included Frederick Ashton (1935) and George Balanchine (1937), both of whom had warned MacMillan of the difficulties in his way, chief among them the lack of obvious relationships between score and scenario. For several critics, MacMillan’s version is the most credible in its engagement with both and in its attempt to reconcile them.

Musically Le Baiser de la fée is a tribute to Tchaikovsky, while its scenario is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s The Ice Maiden. This is the story of a boy destined for immortality because he has been kissed at birth by a fairy, or ice maiden. When the boy grows up and marries, the fairy reappears, entices away him from his bride and carries him away to supreme happiness. Stravinsky explained his fascination with the tale:

“In associating this muse (i.e. Tchaikovsky) with our Fairy, this ballet becomes an allegory. This Muse has in the same way marked the ballet with the fatal kiss whose mysterious imprint is visible in all the work of that great artist.”

Ashton, in creating his version, identified with the idea of the kiss as an ordination, an artistic setting apart. For Ashton the instant of the kiss is the climactic ecstatic moment in the young man’s life. But MacMillan had a far darker story to tell. His instinct was for the bride betrayed. His tale is one of good and evil - of the abandoned bride (“She’s the one who is lost”) and a young man in the grip of everlasting darkness. For Clive Barnes, MacMillan, in reconceiving the allegory, had cut to its heart:

“...the artist in society, the man marked out from his fellows, unable to join in their life and dedicated to suffering”. In MacMillan’s hands, Barnes suggested, the ballet “not only appears as a telling homage to the 19th-century Russian ballets that inspired it, but also as a work full of noble, singing poetry.”

MacMillan was determined that the set should not recycle traditional images of fairyland. Instead, the designer Kenneth Rowell created a threatening landscape in dark mineral colours; an abstract world of rock stratas, gorges, caverns and ominous icebergs.

For Richard Buckle, this Baiser was a ‘tremendous success’. He continued: “MacMillan, with his ear to the ground, has perfectly translated into movement the filigree of shimmering insect splendour which is a feature of this score. Of Lynn Seymour as the Bride, he wrote that she “skims and flits like a happy gnat through her lovely allegretto variation: she has the priceless gift of lending to art an air of spontaneity, and without question makes a triumph of her first created role. Of Svetlana Beriosova as the Fairy, it seemed to Buckle that she had never been seen to better effect in a modern ballet. “As the Fairy, her swooping boreal gestures and Alpine style point the difference between god and human.”

As for The Times, “The criticism that the music, drawn from Tchaikovsky’s salon music, with difficulty sustains a continuous ballet in four scenes is just, but so much invention has been put into the new choreography by Mr Kenneth MacMillan and into the splendid evocative scenery by Mr Kenneth Rowell, that the weakness of the hybrid creation was not obtrusive, for the eye was continuously and abundantly satisfied and gratified.” For Dance and Dancers MacMillan’s greatest success was in transforming nineteenth century classical choreography into “something completely individual and yet at the same time retaining the essence of its style and structure. Le Baiser de la fée represents the most mature choreography MacMillan has so far given us.”

But for Alexander Bland of The Observer. “it is not until the pas de deux that interest quickens, the high point of the evening being soon reached in the fiancée’s solo, a delicious drifting rubato affair, which Lynn Seymour will make into a winner, when she has grown into it. The contrasting dance between the hero and the fairy, which follows (rather awkwardly) immediately afterwards, seems laboured by comparison with Beriosova – serene and fluid as ever, but hampered by a singularly unbecoming costume – not so romantically remote as she might have been. This is an ambivalent role – a kind of amiable Odile – but unattainability is surely in the long run a Muse’s trump card. Donald MacLeary danced and acted excellently throughout.”

Given so many excellent reviews, the question must be asked why the ballet did not survive. The reasons were similar to those for the non-survival in the repertory of Laiderette. MacMillan had wanted to do Le Baiser de la fée as his first commissioned ballet, but the musical demands (configuration) of Stravinsky’s score were impractical for a touring company. When it was produced in 1960 at Covent Garden, the complication became Kenneth Rowell’s set designs. These were so complex that, at a time when the Royal Ballet could call on sixty other works in the repertory, there were only six other ballets with which Le Baiser de la fée could, for technical reasons, be programmed. Of those six some were probably not compatible on the same programme; there could have been a preponderance of opening ballets or middle works, or impossible orchestral demands so Le Baiser de la fée was a nightmare to schedule and had only 33 performances.

First performed: 12 April 1960

Company: The Royal Ballet

Music: Igor Stravinsky

Design: Kenneth Rowell

Cast: Lynn Seymour, Svetlana Beriosova, Donald MacLeary

The Invitation

1960

The Invitation

1960

Late in life Kenneth MacMillan told John Osborne that his experience of seeing Look Back in Anger in 1956 had made him realise that “everything in my world was merely window-dressing.” The Invitation was one of the first fruits of MacMillan’s conviction that ballet in Britain needed grit and realism. It made waves for the quality of its story-telling but what made it especially controversial was its vivid enactment of a rape.

MacMillan had read Colette’s Le Blé en Herbe and The House of the Angel by Beatriz Guido; his scenario for The Invitation, in effect, conflates them. The setting is a bourgeois household ‘in some warm country’ at the beginning of the twentieth century. Two young cousins, a boy and girl, both in the first glimmers of sexual awareness, are seduced by an unhappily married middle-aged couple. While the boy’s seduction might be explained away as a rite of passage, the girl’s experience is brutal. She misconstrues the older man’s interest, and responds almost playfully to him. In a pas de deux, her innocent steps become, in his eyes, overt provocations. He rapes her and she collapses. Later, the boy tried to comfort her; in loathing she pushes him away. Her world has become bestial. She walks ashen-faced downstage as the curtain falls.

Yasmin Naghdi in The Invitation performed 2016 ©Charlotte MacMillan

So explicitly choreographed was the actual rape scene, that Ninette de Valois asked MacMillan at one of the final rehearsals to consider if that part of the action could take place off stage. He declined to make changes and de Valois did not over-rule him. The girl (Lynn Seymour) was flung spread-eagled around her assailant, then hooped around his body, sliding to the ground after the moment of orgasm.

MacMillan opted for a commissioned score by Mátyás Seiber, who died shortly before the premiere (but having substantially completed the score). MacMillan gave Seiber a detailed scenario with a full treatment of the main characters and their psychological states. Only one fragment was not new: Seiber suggested his Pastorale and Burlesque for flute and orchestra, to herald the young girl’s first entry. Again, MacMillan opted for designs by Nicholas Georgiadis: tachiste scenes on gauze praised by most critics, only Peter Williams of Dance and Dancers dissenting, on the basis that the scenery was “near-bordering on the forbidden world of the fairy-tale” and at variance with the harsh realism of the ballet’s subject-matter.

“I made the characters people I know”, MacMillan told The Times, “not the characters in the books. I want people to go to the theatre to be moved by something they can recognise.” For the same paper’s review of the first performance at Covent Garden on 30 December, MacMillan had shown “an altogether remarkable power to represent a terrible act of violence with truth and a gruesome sort of beauty, but without toppling from the abyss of art into the abyss of sensationalism.” Further, The Times noted, The Invitation “established Miss Lynn Seymour’s arrival as an actress-ballerina of the front rank”.

“Choreographically this is MacMillan’s best work and I no longer doubt his quality”, wrote Richard Buckle, a verdict with which his opposite number at The Observer, Alexander Bland concurred. “Above all he has written beautifully for Lynn Seymour. She is the lucky possessor of a tender, expressive, liquid movement astonishingly similar to that of Fonteyn: she can act: and she is very young. From the moment when she runs on and gently plays (flirts would be too grown-up a word) with the boy – sensitively danced by Christopher Gable – to the beautifully arranged twisting rape scene and her last empty gesture, a modern Giselle, fracture by lust instead of by love, he never puts a foot wrong for her. And she responds with a performance which puts her straight into the ballerina class.”

First performed 10 November 1960

Company Royal Ballet Touring Company

Music Matyas Seiber

Design Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast Lynn Seymour, Christopher Gable, Anne Heaton, Desmond Doyle

Orféo

1961

Orféo

1961

Early in 1961 Kenneth MacMillan choreographed the dances for a revival of Covent Garden Opera’s 1953 production of Gluck’s Orpheus. Frederick Ashton had created the dances for the original, but they had been heavily criticised (“Orpheus strolled down the Stygian ranks as if at a revue”) and a decision was made to commission MacMillan instead.

Kathleen Ferrier who sang Eurydice was seriously ill and could sing only two performances; she died later in the year. The production’s designer Sophie Fedorovitch, Frederick Ashton’s close associate, died near the night of the premiere after a gas leak in her flat.

Ballet is intrinsic to Gluck’s opera with The Dance of the Blessed Spirits one of its musical highlights. According to The Times’ opera review, “Kenneth MacMillan’s choreography was not always well suited to the music, notably in the E flat major dance in the first scene, but he seemed more at home in the Elysian Fields, where Miss Anne Heaton and Mr Alexander Bennett led the blessed spirits’ sedate revels”.

Philip Hope-Wallace, writing in The Guardian, was more critical. “Kenneth MacMillan’s choreography comes no nearer than most efforts to solving the problems of the ballets: indeed it looks leggy, fidgety, and the costumes adopted suggest the more sensational Wimbledon outfit.

Seven Deadly Sins

1961

Seven Deadly Sins

1961

Elizabeth West and Peter Darrell co-founded Western Theatre Ballet in 1957. They aimed to find new audiences for ballet, performing in theatres that large companies did not visit. It was their ambition to commission ballets reflecting the spirit of the day and, crucially, to revitalise ballet’s theatrical dimension (hence the word ‘theatre’ in the company’s name). Lord Harewood’s invitation to perform at the Edinburgh Festival in 1961 was an important recognition of what Western Theatre Ballet had achieved. The programme they chose was daunting for a small company: Kenneth MacMillan’s version of Brecht/Weill’s Seven Deadly Sins, along with Salade choreographed by Peter Darrell and Le Renard choreographed by Alfred Rodrigues. A particular strength of the evening was the designs, which for all three ballets were overseen by Barry Kay. Ian Spurling was MacMillan’s designer, his set constructed, rather than consisting of painted cloths and flats, the seven locales of Anna’s sins announced on large lettered cubes moved around the stage by the cast.

The Seven Deadly Sins, which Berthold Brecht and Kurt Weill wrote after they fled Nazi Germany (it was their final collaboration), is an excoriating assault on capitalist morality. It was conceived as a satirical ballet chanté and first commissioned by Boris Kochno and George Balanchine in 1933. The work had been largely forgotten until Balanchine revived it in 1958.

Its heroine, Anna is a split personality, presented in MacMillan’s ballet as two sisters. The singing Anna is all rational calculation. Her counterpart, the dancing Anna, is instinctive, natural, unguarded and generous. Anna is despatched into the world to ‘make good’. The deadly sins from which her sister has to save her are the instincts that stand in the way of success. The two sisters, really one, journey around the America of Brecht’s imagination encountering a different sin in each city. Each humane impulse of the dancing Anna (Anya Linden) is stigmatised as a deadly sin by the singing Anna’s voice of reason (Cleo Laine). Virtue subsists only in acquiring money, symbolised by the home in Louisiana to which they eventually return.

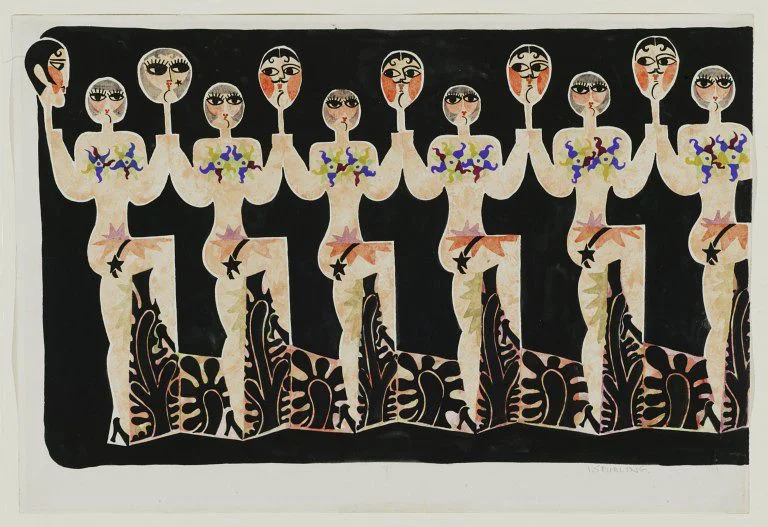

©Ian Spurling Costume design for Corps de Ballet of Seven Deadly Sins 1961

Lotte Lenya was to have been MacMillan’s Singing Anna, as she had been both in the 1933 and in the 1958 revivals. She had not understood that the choreography would be new and withdrew from the production to be replaced by Cleo Laine. For The Times the ballet made the strongest impression of the evening. “Whether or not we agree with Brecht”, the review (unsigned) continued, “that there is anything specifically bourgeois about this immorality, the piece should make us profoundly uncomfortable. That it did not tonight was partly due to Mr Kenneth MacMillan’s and Mr Ian Spurling’s all too brilliant evocation of the world of Pabst’s films, which now seem safely quaint, and partly to the invincible warmth of Miss Cleo Laine’s singing. The final horror should lie in the fact that Anna I thinks of herself not as hard-bitten but as a pillar of morality: no room here for a heart of gold, or even a heart at all.

A music critic, Peter Heyworth reviewed the premiere for The Observer. “What was conceived in rage is swaddled in pity and savage satire is reduced to piquant paradox.” However, Andrew Porter of The Financial Times came to MacMillan’s defence. “It is not The Seven Deadly Sins, one feels, that Brecht and Weill intended. On its own terms, however, if not on theirs, MacMillan’s choreography is filled with brilliance and invention and the whole presentation, in Ian Spurling’s extremely clever set, is exciting.”

- 1961

- Western Theatre Ballet, Edinburgh Festival

- Music Kurt Weill

- Design Ian Spurling

- Cast Anya Linden, Cleo Laine

Diversions

1961

Diversions

1961

Kenneth MacMillan choreographed Diversions to fill a last-minute gap in the first triple bill of the Royal Ballet’s 1961-’62 season. Ninette de Valois appealed to MacMillan to fill the breach. He agreed despite the pressure on him to complete another work, Seven Deadly Sins, for Western Ballet Theatre (the premiere of which was on 4 September). Little choice was given him about the shape of the work; it had to be plotless as the programme already had two narrative pieces, Frederick Ashton's Persephone and Alfred Rodrigues’s Jabez and the Devil. Neither was the score MacMillan’s choice; De Valois suggested Arthur Bliss's Music for Strings (de Valois's own Checkmate was also created to music by Bliss). With little time to seek an alternative score, MacMillan agreed to use Bliss.

Diversions is choreographed for two leading and four supporting couples. According to Edward Thorpe, MacMillan’s earlier biographer, when The Royal Ballet revived the piece in 1979, MacMillan remarked to him that he was amazed that, 18 years before, he had dared to demand such sustained virtuosity from his dancers.

Diversions was an exercise in neo-classicism of a kind by then familiar to MacMillan. Audiences who knew nothing of the background were surprised by the choice of Bliss as composer and of MacMillan’s ‘softening’ of his accustomed angularities to suit Bliss’s more traditional textures. The choreography is for two contrasting couples; one couple seem abstracted – almost ceremonial (Svetlana Beriosova and Donald MacLeary). In contrast to their ‘diffident grandeur’ (Clive Barnes’ description) is a more darting exuberant couple, who may be alter egos (Maryon Lane and Graham Usher). Four subsidiary couples frame the various pas de deux.

“Following the hint of the music”, wrote The Observer’s Alexander Bland, “MacMillan has concentrated on smoothness. There is no echo here of his early jerky, perky style. This is the purest classicism. There is hardly a step, which is not from the classroom, yet not a cliché.” Bland also noted parallels to Frederick Ashton’s Symphonic Variations; this was also commented on in the (unsigned) Times review. “MacMillan’s choreographic idiom has taken a glance, if not a step backward, to the Ashton of Symphonic Variations, as though to check his development with the style of a senior colleague.” Peter Williams in Dance and Dancers suggested that if Symphonic Variations was a song of spring, that Diversions was its autumnal equivalent.

However, The Guardian’s un-named critic (possibly James Kennedy), characterised both Diversions and Jabez and the Devil, its companion piece in the programme as “the journalism of choreography – good, sound hack work, required by the repertory, but not born, apparently of any passion in their choreographers’ hearts”. Mary Clarke, writing in Dancing Times saw “hardly a quirk of MacMillan’s wry imagination.” She expressed surprise at MacMillan’s choice of music (“or if he did not choose it, (it is) surprising that he accepted the commission.” There was approval, however, from Clive Barnes at Dance and Dancers, who commented on “the refinement and exciting power of the choreography as a whole. It seems to spin out in one effortless and elegant thread.”

Philip Prowse’s designs (no doubt as hastily improvised as the ballet itself) came from a palette of aubergine, black, ochre and cinnamon, the women’s bodices and skirts and the men’s tunics possibly Minoan or Etruscan in inspiration For Peter Williams in Dance and Dancers it was “though Gods, or surviving mortals were performing some ritual in the ruins of a civilisation.”

As originally conceived, Diversions was to be performed only in blacks and practice dress, which suggests MacMillan thought of it an exercise in pure dance. At some point someone had second thoughts and designs were commissioned from Philip Prowse to a limited budget which laid down the use of only three flats. He turned the three flats into suspended borders of massive architecture, and set against them costumes with his characteristic creation of planes and shapes within the body outline, predominantly in brown, an uncommon colour on the dance stage.

The Royal Opera House’s annual report for 1961-62 noted that of the three ballets commissioned in the season, two, Ashton’s Persephone and MacMillan’s Diversions had become part of the permanent repertory Diversions was occasionally revived during the 1960s and in 1979 and performed by the Royal Ballet New Group in 1971. In 1999, Scottish Ballet revived the ballet with new designs by Philip Prowse.

- Royal Ballet, Royal Opera House

- Music Arthur Bliss

- Design Philip Prowse

- Cast Maryon Lane, Svetlana Beriosova, Donald MacLeary, Graham Usher

The Rite of Spring

1961

The Rite of Spring

1961

In 1962 Kenneth MacMillan became the nineteenth choreographer to attempt The Rite of Spring and one of the few to have done so with any success. Nijinsky’s original for the Diaghilev Ballet was only performed seven times: Stravinsky took a poor view of it and thereafter viewed The Rite as essentially a concert work. Whatever the merits or otherwise of Nijinsky’s choreography, one truth remained: that he had made the first ballet to have broken with academic technique and The Rite of Spring became a beacon of all that was modern.

MacMillan’s commission from the Royal Ballet came about almost by accident. Jerome Robbins had been asked to make a version of Les Noces to mark Stravinsky’s eightieth birthday. When he withdrew, MacMillan’s proposal for a new Rite was substituted. By 1962 Stravinsky loomed conspicuously large in Kenneth MacMillan’s music choices and it was his fifth ballet to a Stravinsky score.

The original work stemmed from the Diaghilev Ballet Russes’ fascination with Russia’s mythic past. In Stravinsky and Nijinsky’s scenario, a prehistoric people from the forests of Northern Russia sacrifice a virgin to the cosmic forces, which alone can make the spring come and ensure the continuity of the tribe. The scenario was retained by later choreographers including MacMillan. His innovation, was to switch hemispheres and, in tandem with his designer, Sidney Nolan, to re-enact The Rite in a nightmarish vision of aboriginal Australia. Nolan called the golden mushroom like totem pole on the backcloth of the second scene ‘Moonboy’, but to Cold War audiences it seemed like the cloud of a nuclear bomb explosion. The dancers wore ochre red and brown unitards, marked with handprints, suggestive of the daubed bodies of aboriginal peoples.

There are inherent problems in choreographing Stravinsky’s score. Its climax is powerful, but the early dances can be ritually static. MacMillan abandoned these highly nuanced rituals in favour of dramatic effect. The ballet’s complex choreographic patterns mean that it is best seen from above. MacMillan’s Rite is one of the few ballets to have a specially designed floorcloth.

“Mr MacMillan’s invention can never have been more musical or assured”, said The Times of the opening night Gala, attended by Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret. “ Time and again Stravinsky’s music, unaffectedly conducted by Mr Colin Davis meets its match, as the choreography, with its blend of primitivism and modern jive, piles climax on climax. At first sight, a thrilling ballet to which we will gratefully return.” “Alexander Bland of The Observer thought MacMillan’s new ballet a ‘really solid addition’ to the repertoire of a kind different from anything else. “Once the idiom of stage spectacle has been accepted, one can give nothing but praise. The profusion of invention and the way in which a new but not offensively quirkish style of movement is sustained is extraordinary. The company shows up excellently. Nolan’s sets are impressive and Monica Mason gives a tremendous performance as the sacrificial girl.”

Her performance as the Chosen One, made Monica Mason’s career. “A maiden excellently chosen”, wrote The Guardian’s critic. “She looks just a little more statuesque than most of her companions and she moves with an apparently easy grasp of the music’s rhythms and with a lissom authority.” The review continued. “Choreographer and designer have been at one: they have made sense – emotional sense.”

- First Performed: 3 May 1962

- Company: Royal Ballet, Royal Opera House

- Music Igor Stravinsky

- Design Sidney Nolan

- Chosen Maiden Monica Mason

Dance Suite

1962

Dance Suite

1962

Dance Suite was a commission for the Royal Ballet School’s end of year performance in July 1962. Ten of the graduating students were joining the Royal Ballet and the various reviews singled out two dancers who would feature significantly in Kenneth MacMillan’s ballets in the years to follow.

The Guardian’s (un-named) critic wrote: “Kenneth MacMillan’s dance suite to the music of Darius Milhaud was very apposite in its bouncy gaiety. It gave something to many dancers and most to Vergie Derman, a tall blonde South African, who promises to be an athletic virtuoso rather in the Balanchine manner.”

The Times thought that the “folk-dance flavoured choreography would have daunted all but the stoutest hearts among professional dancers” and singled out Derman along with “Mr Richard Cragun, a young man of considerable promise whose American nationality makes him unfortunately ineligible for our national ballet.”

- 14 July 1962

- Royal Ballet School, Royal Opera House

- Music Darius Milhaud

- Cast Vergie Derman, Richard Cragun, Kerrison Cooke

Fantasia in C minor

1962

Fantasia in C minor

1962

Kenneth MacMillan made this solo for Rudolf Nureyev. The occasion was a gala matinée, which Margot Fonteyn had organised in aid of the Royal Academy of Dancing (as it then was). But during the performance on a slippery stage Nureyev lost one shoe, stopped (“with devastating sang-froid”) to remove the other and appeared thereafter to improvise the choreography.

Writing in The Observer, Alexander Bland (Nigel and Maude Gosling, Nureyev’s close friends) characterised Fantasia as a “vaguely hip arrangement performed by Nureyev with a nonchalant ease which enabled him to shed a pair of recalcitrant slippers without subtracting from - indeed adding to - the choreography.” The Times was more chilly: “one could have been forgiven for imagining that this was the incredible Mr Nureyev’s benefit”. It said the solo was “new, jazzy, but misjudged.”

“I was not proud of the choreography”, MacMillan told Edward Thorpe. He was uncomfortable with Nureyev and with the cult of celebrity that surrounded him.

Symphony

1963

Symphony

1963

Choreographers using symphonies as ballet scores had long been controversial. The first was Leonide Massine who, in 1933, aroused considerable debate by his use of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony for Les Présages and Brahms’s Fourth Symphony for Choreartium. In 1939, he had used Shostakovich’s First Symphony for Rouge et noir, with a scenario about Man and his Destiny. Few followed in his footsteps and by 1963 the symphonic ballet was out of fashion. Whatever MacMillan may have felt about revisiting a defunct idiom, he was under pressure to produce a steady stream of work for the Covent Garden stage. He turned for advice to John Lanchbery, who suggested Shostakovich’s first symphony, written in 1926 when the composer was 19.

Unlike Massine’s version, MacMillan’s was - ostensibly - plotless and, unlike Massine, Macmillan did not seek to lay the score out on stage with a close equivalence between dancers and individual instruments of the orchestra. In some ways Symphony resembled MacMillan’s own 1961 ballet Diversions, the idiom similarly neo-classical. As in Diversions, there were two lead couples and a group of soloists (here, three subsidiary couples); however, Symphony had a full corps de ballet.

Despite the lack of stated plot, it was easy to imply relationships among the dancers. Sibley, lying sphinx-like on the floor was confronted first by MacLeary, then by Doyle. A pas de deux converted to a pas de trois, leaving the second woman outside the triangle. There were forceful traverses for the corps, in Clive Barnes’ words, “when Shostakovich says jump, they all jump”. Throughout, Barnes wrote for Dance and Dancers, “there is a feeling of lovers in innocence and lovers in experience. At times the ballet might well be about loss of virginity, at others loss of identification, at others still loss of human contact. This desolate undertow finds its final expression in the closing sculptural group. Here you find the two men locked in a sort of combat, with the ‘Sibley’ girl emerging from the group with her empty arms outstretched for contact, and the ‘Parkinson’ girl at the back, her arms raised aloft in despair or even horror”.

This last figure may even have stood for MacMillan himself. In an interview beforehand with the Covent Garden Friends’ magazine About the House, MacMillan had said “The more I look at my work, the more it seems that, unwittingly, I choose the lonely, outcast, rejected figure: The Invitation, Rite of Spring, Solitaire, Le Baiser de la Fée. I don’t set out to do it, but it always seems to happen unconsciously – as a sort of leitmotif. It will be interesting to see if it emerges in the new work.”

The designer Yolanda Sonnabend had been introduced to MacMillan by her mentor Nicholas Georgiadis; her designs for Symphony, vast painterly backdrops, had afterimages of Georgiadis’s previous designs for The Invitation (1961); “The soft floating backcloths are gorgeous splashes of colour”, wrote Mary Clarke in the 1964 Ballet Review, “but her costumes, although serviceable for dancing, are unattractive and unbecoming, robbing their wearers of character”. Peter Williams, writing for Dance and Dancers, thought the “lack of relation between costumes and settings curious from a talented painter.” (Sonnabend modified the designs when Symphony returned to the repertory in 1975).

There were illnesses among the cast; Antoinette Sibley was a last-minute replacement for Lynn Seymour, who had flu, while Donald MacLeary had a knee operation during rehearsals. Nonetheless, Clive Barnes was fulsome about the first night. “With its incandescent excitement contrasted with its sudden shafts of inexplicably desolate poetry, Symphony is a work of obvious distinction”, he wrote in The Times. Less warm was The Observer’s Alexander Bland. “The choreographic design is never clear. The principals don’t form, either as individuals or pairs, strongly characterised motifs.” The Guardian’s review (unsigned) was tepid; “neo-classical dance, laced admittedly with some MacMillanesque contortions but apparently unencumbered by any purpose save that of catching the mood and the rhythm of the music in apposite dance”.

Several years later, there was an intriguing back-reference by James Kennedy of The Guardian. When, eventually, Song of the Earth came to be staged at Covent Garden, he characterised MacMillan’s classic as ‘the marvellous fruition’ of such ‘half-baked experiments’ as Symphony.

Las Hermanas

1963

Las Hermanas

1963

Kenneth MacMillan created Las Hermanas ('The Sisters'), for Stuttgart Ballet. Like Lorca's play The House of Bernarda Alba on which it is based, Las Hermanas is a tense psychological drama about sensuality under harsh repression and the emotional and violent consequences that follow. It tells the story of five sisters, all unmarried, who have been cowed into conformity by their tyrannical mother. The eldest is engaged, but the family is torn apart when her fiancé is seduced by her youngest sister. A third sister betrays them. The fiancé is banished, the elder sister is condemned to a lonely spinsterhood and the youngest hangs herself in shame.

MacMillan had to persuade audiences that dance could be as apt a medium for the story as the spoken word. In the event, his choreography stretched ballet to new limits of dramatic expressiveness. “It is classical, certainly, in its language but transmitting classicism into ferocious drama.” wrote James Kennedy in The Guardian. According to Monica Mason, "Kenneth would have been hugely attracted by the claustrophobia of this house and these young repressed women; it was right up his street."

It was the designer, Nicholas Georgiadis, who suggested to MacMillan the balletic possibilities of Lorca’s original. Georgiadis’s highly realistic set, the distillation of Lorca’s oppressive atmospheres, is like a cloistered prison and follows the playwright’s instructions exactly. “A very white room in Bernarda Alba’s house. The walls are white. There are arched doorways with jute curtains....” Frank Martin's score is similarly apt, the sound world described by the solo harpsichord eerily claustrophobic.

MacMillan had an outstanding first cast in Stuttgart that included Marcia Haydée, Birgit Keil and Ray Barra. At the outset, the principal characters are strongly established; the elder sister’s introversion with clenched fists, and a contrapuntal use of upper and lower body; the jealous sister with waspish meanness, quick turns, and accusing arms. Once the younger sister has tried on her sister’s wedding veil, an atmosphere has been created, the scene set for what is to come. The groom has an animal insolence but in the pas de deux with the bride-to-be, she is spinsterish, all rigid arms and tight fists. She shrivels when she realises they are being watched. Then the groom dances with the younger sister – this time the dance is abandonedly sexual. The jealous sister tells the household. The denouement follows and the mother banishes the groom; the sisters contemplate a bleak finality. The youngest sister is discovered hanging as the curtain falls.

Reviewing the Stuttgart production at the Edinburgh Festival later that year, The Times reviewer (un-named but almost certainly Clive Barnes) wrote that “MacMillan's use of literature tends towards the cavalier and this ballet is no exception, but he has extracted from the Lorca play an imaginative libretto of considerable dramatic impact.” Alexander Bland, reviewing the 1971 Sadler’s Wells production for The Observer, noted that Lorca’s original had been “translated into dance terms with a sustained intensity”. But James Kennedy, reviewing Western Theatre Ballet’s 1966 production in The Guardian cavilled at the depiction of the younger sister’s suicide; “a shock all right, but not the right sort of shock in the context.”

In 1966 Peter Wright directed a BBC2 studio version of Las Hermanas. “I brought over Marcia Haydée and Ray Barra, along with some dancers from the Royal Ballet, including Georgina Parkinson and Monica Mason. While keeping to the actual set designed by Georgiadis, I was able to enlarge it and make it much more as if it had been created for television rather than for the theatre. One could get in close to the action. It worked extremely well.”

In 1966 Las Hermanas entered the repertoire of Western Theatre Ballet and in 1971 that of the Royal Ballet New Group. It was most recently performed by Sarasota Ballet in Florida in 2007.

Dark Descent

1963

Dark Descent

1963

Kenneth MacMillan choreographed the short chamber ballet Dark Descent for the ITV arts series Tempo, produced in Birmingham, which was shown late on Sunday nights and presented variously by Lord Harewood and the actor Leonard Maguire. The programme showed MacMillan working with Marcia Haydée and Ray Barra from Stuttgart Ballet and answering questions about his method of working. He based the ballet, an extended pas de deux, on the Orpheus myth and on a grieving husband’s pursuit of his dead wife to the underworld. Following their collaboration on Dark Descent, MacMillan asked the programme’s designer James Goddard to work with him on his next ballet, La Création du Monde.

Tempo (the predecessor of LWT’s Aquarius, which in its turn begat The South Bank Show) was an attempt to challenge the BBC’s hegemony in arts magazine programmes. This edition of Tempo was one of the ITV network’s earliest broadcasts of classical dance. For a time, the dance scholar Peter Brinson was the programme’s editor.

In 1982 the director Jack Gold followed a somewhat similar format to that of Dark Descent, when he filmed a documentary for ITV’s Granada region on MacMillan rehearsing two other dancers from Stuttgart Ballet. A Lot of Happiness, the programme’s eventual title, also had parallels to Dark Descent in its invocation of the Orpheus myth.

La création du monde

1964

La création du monde

1964

“Kenneth MacMillan has owed us a light-hearted ballet for years”, began Clement Crisp’s review of Kenneth MacMillan’s La Création du Monde. It is a whimsical version of the Creation story in the form of a zany children’s game.

Darius Milhaud’s score, much influenced by black music and jazz, was originally written for the Ballet Suédois, for which Jean Borlin had staged his version in 1924. In its day it was described as a ballet Nègre, because of its supposed sources in the African imagination of the beginnings of life. In 1931 Ninette de Valois had choreographed a distinctly solemn staging for the Camargo Society, which was later performed by the Vic-Wells (now Royal) Ballet.

Solemnity was the last thing, however, on MacMillan’s mind. His Création was the Royal Ballet’s first experiment in pop art. For early peoples, he substitutes children at play on whom the curtain rises as they empty out the contents of a dressing-up box. Then a decrepit “Great Deity” with an enormous top hat is wheeled on-stage in the delivery basket of a butcher-boy’s bicycle. The Great Deity, in Union Jack-bedecked white tights is introduced, rather like a conjuror at a party. The games begin.

“For my next creation”, flashes a message on a screen and the animals enter. Then the screen signals; “And now INSTANT people”. Enter Adam and Eve (Richard Farley and Doreen Wells). Their fig leaves are discarded for all-over white tights. Eve’s are stencilled with the words ‘bird’, ‘floosie’, ‘doll’, ‘fluff’ ‘chick’, ‘filly’ ‘bint’, ‘frail’; Adam’s – less controversially - with ‘bloke’, ‘fellow’, ‘beau’, ‘butch’, ‘homme’.

Then, as Clive Barnes recorded for Dance and Dancers, followed a pas de deux for Adam and Eve. “This involves eccentricities, including much laying on of innocent hands on innocent anatomies in a mildly exploratory mood. Of course the answer to the rude question ‘has no-one ever told them?’ is no. Paradise is broken by the entrance of the Serpent (Elizabeth Anderton – “I was a teenage snake”) who comes on jauntily sucking her thumb. The Deity tries to fight her off while Adam and Eve resume their supernal fumblings. The Apple enters (a dancer in a green balloon --‘Granny’, ‘apple’, ‘fresh today’) and the Serpent jives with him. She tempts Adam and Eve to take a bite from the Apple (while the subtitles joyfully proclaim ‘I was seduced by Granny Smith’) and they nibble the unfortunate Apple down to the core.”

The ballet ends with Adam and Eve’s pas de deux becoming more enthusiastically sexual. God interrupts their revels and chases them away with a whip. As God is left disconsolately alone, the children mock him and he is ferried away on the butcher’s bike.

“This is a ballet full of ideas”, wrote Clement Crisp in The Financial Times, “of gimmicks taken from ‘Pop’ art but made completely balletic and the tricks and comic devices never obscure the basic strength of the dancing.” “Certainly it is all very jolly”, wrote The Guardian’s critic James Kennedy, “and iconoclastic and cynical as well. For if this new version can be said to have anything like a message, that message can only be that the ‘Great Deity’ made a pretty mess of his creation.”

MacMillan invited James Goddard, the designer, to work on the ballet, following their previous collaboration on MacMillan’s television ballet Dark Descent. “The decor is perfectly in key with the work”, wrote Clement Crisp. Richard Buckle dissented: “It is high time Pop art reached ballet, but James Goddard is rather a confused and wishy-washy kind of Pop artist to represent it.” Peter Williams, writing for Dance and Dancers, praised MacMillan’s intent in choosing Goddard, but cavilled at the result. “In an art so composite as ballet with at least three creators doing their nut, there is really only room for one comedian who should, by rights, be the choreographer.”

Richard Buckle’s review for The Sunday Times ended: “God creates man in his own image, then man creates God in his own image. Man mocks God and sends him packing: and God starts all over again. But who created God in the first place? I see no reason why these sublime considerations should not be treated in a Pop and jazzy way.”

Divertimento

1964

Divertimento

1964

This was the only pas de deux that Kenneth MacMillan ever created for Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev. Its single performance was the high point of a gala evening at the 1964 Bath Festival, whose director was Yehudi Menuhin. On the day of the performance Fonteyn heard that her husband, Roberto Arias, had been seriously wounded in an attempted assassination. She decided to dance at the performance before leaving for Panama to be at his side.

Fonteyn and Nureyev had rehearsed the pas de deux several months previously before leaving on a tour of Australia. The photographer Keith Money recalled their rehearsal in Bath, along with a moment of naivety from Menuhin about the nature of choreography.

“Rather surprisingly the dancers had somehow remembered most of the work during the interim, and the first stage rehearsal was progressing satisfactorily when Menuhin suddenly stopped playing, waved his bow at the two dancers, and said: ‘I think, here, something a little lighter, more cheerful, perhaps’.”

The Alexander Bland column in The Observer recorded the eventual performance as follows.

“That a gala audience in the English provinces, faced with a modern dance arrangement, to a bit of unaccompanied solo violin by Bartok, should respond not with an icy rattle of gloved hands but with determined shouts for an immediate encore is surely a signal worth noticing. Is public taste on the move? The presence and playing of the Festival director, Yehudi Menuhin certainly contributed much: the dancing of the extraordinary couple contributed more; but most credit must go to the choreographer, Kenneth MacMillan, who showed again that he has not only found a personal style but that he can deploy it to exploit his dancers’ virtues. This short piece, written in the sinuous, emotional groping á terre style of the best bits of his recent Images of Love was proved a success, all the keener for being so improbable.”

Images of Love

1964

Images of Love

1964

Images of Love was one of two ballets commissioned for a Covent Garden triple bill to mark the four hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. The other works on the programme were Frederick Ashton’s The Dream and Robert Helpmann’s 1942 ballet Hamlet.

MacMillan’s ballet was a suite of vignettes about unsatisfactory love affairs. The individual episodes, nine in all, were based on speeches from Shakespeare’s plays – four from Two Gentlemen of Verona - and on Sonnet CXLIV (“Two loves I have of comfort and despair.”). A few lines, common to each the word ‘love’, were spoken by the actor Derek Godfrey (on tape) before each dance

“The idea of this deliberately episodic ballet was good but perilous”, wrote The Guardian’s critic James Kennedy.”The quotation before each episode promised, or seemed to promise, something new and different each time; but seven times out of ten, the promise was unfulfilled. It is difficult enough to make a good one-act ballet; but to make eight short ballets, each with a sharp choreographic point, is more difficult still.

“Once again”, wrote Clive Barnes for Dance and Dancers, “MacMillan has based his ballet on the character of the ‘little girl lost’, although here this MacMillan familiar is given for the first time to a male dancer, and the Rudolf Nureyev role, miserably alone in a world of miserable loveless couples, could perhaps have been used to bring the ballet into sharper focus.”

photo courtesy of the Barry Kay Archive

MacMillan’s character sketches are often intriguing”, The Times music critic reported, while Alexander Bland of The Observer had praise for individual vignettes. “Two at least are original, moving and beautiful. A legato “love is blind” pas de deux for Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable is written as though the two lovers, seeing only through their bodies, were drowning in a sea of sensuousness.; and a slow pas de trois in which Nureyev joins the same pair to become the apex of the sinuousness triangle celebrated in the “two angels” sonnet, exploits a new and fascinating Oriental plasticism. Both were superbly danced.”

The specially commissioned score was by Peter Tranchell, a Cambridge music lecturer. For Noel Goodwin of Dance and Dancers, it was little more than an accompaniment which failed to amplify character and had “the semblance of sound-track music”. For James Kennedy of The Guardian, it was “emphatically not the food of love.”

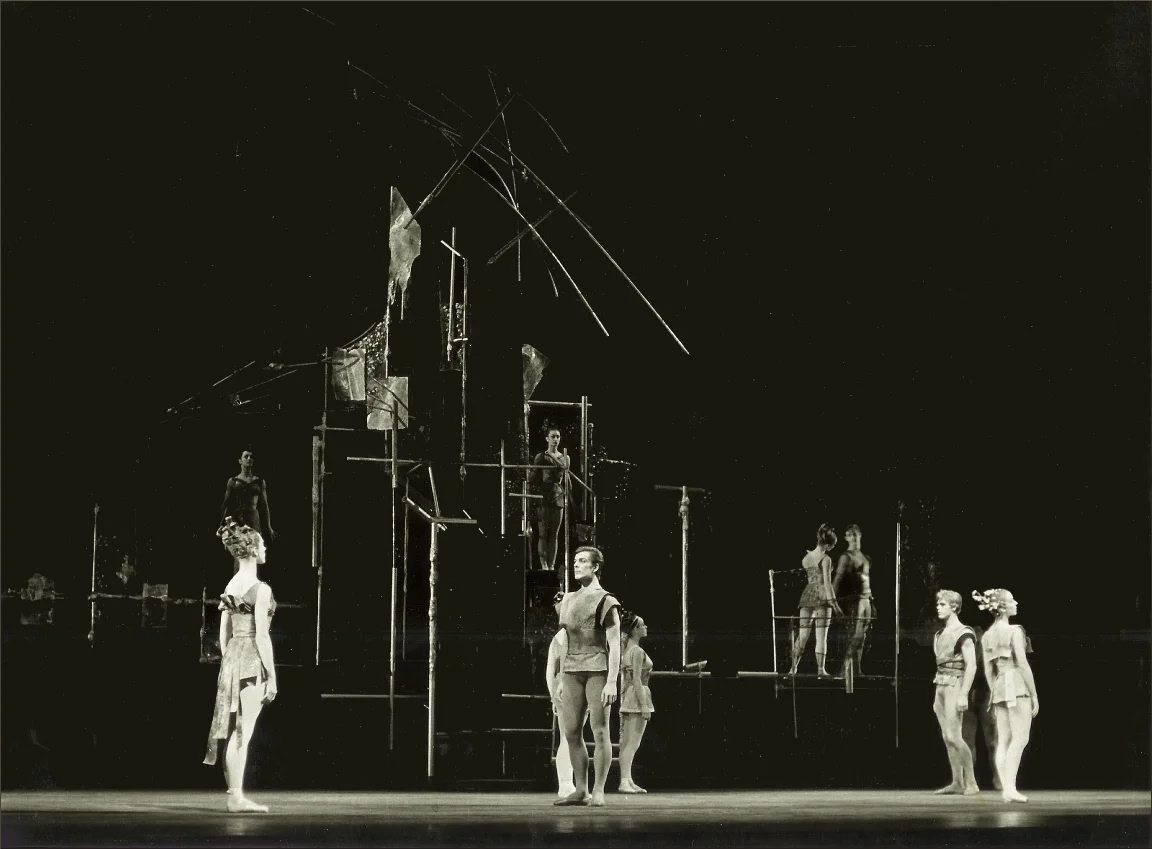

For Images of Love, Barry Kay created a multi-level tubular construction. MacMillan had originally seen Kay’s work in the theatre and been particularly struck by his mastery of period costume design. MacMillan acknowledged that working with Kay made his job so much easier, the clear, yet imaginative designs helping to clarify his own often vague ideas during the creating of the ballet. Also, importantly, they shared a similar response to music. MacMillan remembered Images of Love’s set being “for me a breakthrough in 3-dimensional stage design” although it was rather a 3-d backcloth than a setting within which the dancers moved. The 1960s was to see the development of built sets rather than backcloths for ballets, notably Las Hermanas (1963) and Romeo and Juliet (1965), both designed by Georgiadis.

Of the set, Kennedy wrote that “Barry Kay’s bamboo edifice, in the background to this work, was alluring”. Peter Williams of Dance and Dancers agreed about its visual beauty, but argued that it distracted from the dance. “What Kay has done for Images of Love seems to belong to the designer trying his hand at sculpture rather than a sculptor bringing his own plastic sense to choreography.”

Romeo and Juliet Pas de Deux

1964

Romeo and Juliet Pas de Deux

1964

When Kenneth MacMillan’s ballet Romeo and Juliet was still in gestation, and before the management at Covent Garden had given the go-ahead, Lynn Seymour was invited to appear on CBC television in her native Canada. She asked Christopher Gable to join her on the programme. Inelegantly billed as Lynn Seymour, Our Dancing Export, it was described as “an incisive profile of the Canadian ballerina”. For the occasion, MacMillan offered to create a pas de deux from his envisaged production.

In her biography, Lynn Seymour recalls:

“In rehearsal Kenneth created a pas de deux which serves as the fulcrum for his work. Christopher and I – both in fine fettle – responded to what Kenneth wanted as if we three were under a potent spell. Like a man possessed, Kenneth completed the balcony pas-de-deux in three rehearsals”.

Shortly afterwards, MacMillan received the go-ahead for a full production of Romeo and Juliet. The commission for CBC meant that a key part of the eventual ballet’s architecture was already in place.

Romeo and Juliet

1964

Romeo and Juliet

1964

MacMillan had been longing to create his own Romeo and Juliet after seeing John Cranko’s version for the Stuttgart Ballet. Lynn Seymour had danced Cranko’s Juliet as a guest artist in Stuttgart in April 1964; MacMillan had subsequently choreographed the balcony scene pas de deux for her and Christopher Gable to perform on Canadian television during their summer break that year.

Frederick Ashton, then artistic director of the Royal Ballet, gave MacMillan the green light for the complete ballet in September 1964. The company wanted a big new three-act ballet based on the play by Shakespeare, whose 400th anniversary was celebrated in 1964. Ashton had chosen not to mount the Romeo and Juliet he had made for the Royal Danish Ballet in 1955, fearing it would suffer by comparison with the large-scale Lavrovsky production the Bolshoi Ballet had brought to the Royal Opera House. MacMillan therefore had less than five months to create his first three-act ballet, which the company hoped to include in its 1965 American tour.

He, Seymour and Gable endlessly discussed their ideas about the characters as MacMillan choreographed the key pas de deux in each act – his starting point around which the rest of the ballet would be built. He and Seymour envisaged Juliet as a headstrong, passionate girl who makes all the crucial decisions: the secret marriage, in defiance of her parents’ wishes; taking Friar Lawrence’s potion; joining Romeo in death. Gable’s Romeo was a young man swept off his feet by love, dancing in dizzy exultation.

Romeo and his close friends, Mercutio and Benvolio, were given bravura steps that distinguished them from the street fighters in Verona’s market place and the stately aristocrats in the ballroom scene. MacMillan had hitherto avoided virtuoso steps because he thought them too conventionally balletic. Only Juliet and her girlfriends are on pointe: their choreography is contrasted with character dances and verismo crowd scenes. MacMillan broke the ballet conventions of the time by having the dancing evolve from naturalistic action. Unlike Cranko’s production, there are no picturesque poses for applause at the end of set-pieces. Unlike the Bolshoi production there are no spotlit entrances for the leading characters: Romeo is discovered in semi-darkness at the start of the ballet as Rosaline’s anonymous suitor; Juliet’s arrival at the ball in her honour goes unnoticed at first.

MacMillan wanted to show the lovers as youngsters at the mercy of a powerful patriarchal society. Georgiadis’s monumental designs – unusual, then, for a ballet – emphasised the oppressive might of Juliet’s surroundings. She is a small, vulnerable figure within the imposing Capulet household and, finally, laid out in the family vault. Even Friar Lawrence is to be found in a well-appointed monastery rather than a simple cell. Georgiadis and MacMillan took their inspiration from Italian Quottrocento paintings and architecture, as well as from Shakespeare. Franco Zeffirelli’s 1960 production of Romeo and Juliet for the Old Vic had been another influence, with its fortress of a palazzo guarding the Capulet family’s treasures – including their nubile daughter.

MacMillan borrowed from Cranko the harlots who animate the market-place scenes. It is they who get the action going in the first scene, as they roister with the three young bloods, Romeo, Mercutio and Benvolio, and provoke the indignation of the townspeople. Tybalt, one of the Capulet clan, provokes a fight with the Montague faction which develops into a lethal brawl. The Prince of Verona enters to put a stop to the fighting, commanding the warring factions to lay down their swords.

The second scene introduces Juliet, playing childishly with her nurse. Her parents enter with Paris, her intended bridegroom. When they leave, the nurse tells her gently that her girlhood is over.

The Capulets are giving a ball to mark Juliet’s entry into Veronese society. Romeo and his two friends decide to crash it, wearing masks as a disguise. During the formal dances, Juliet and Romeo fall in love before she realises that he is a Montague, a family enemy. When his identity is revealed, Lord Capulet intervenes to prevent Tybalt breaking the laws of hospitality by starting a fight.

After the ball, Juliet is on her balcony, dreaming of Romeo, when he enters below. She runs to join him in an ecstatic pas de deux expressing their love for each other.

Kennth MacMillan in rehearsal with Margot Fonteyn and Rudolph Nureyev

In Act II, Romeo is a changed man in the market place, no longer at ease with his companions and the harlots. A wedding procession passes through, with acrobats entertaining the crowd to the sound of mandolins. The nurse arrives, bringing a letter for Romeo from Juliet, proposing a secret wedding.

Friar Lawrence marries the lovers, with Juliet’s nurse the only witness. Before the marriage can be consummated, Romeo is embroiled in a duel with Tybalt in the market place. Because Romeo had initially refused to quarrel with Tybalt, Mercutio had stepped in for a dare-devil sword fight, only to be stabbed in the back. Romeo avenges his dead friend, killing Tybalt in anger. He has to flee when Lady Capulet enters, overcome with grief, followed by her husband.

Act III opens in Juliet’s bedroom, the lovers asleep together. Romeo realises dawn is breaking and that he should leave. Juliet, frantic, tries to delay him, knowing he must go into exile. He departs just before Juliet’s parents arrive with Paris. Juliet rejects him, to her father’s rage, but she will be forced to marry him. In a dilemma about what to do, she sits on her bed, confounded, then rushes to seek Friar Lawrence’s help.

He gives her a potion that will send her into a death-like trance. Romeo is to be told of the plan so that he can rescue her from her tomb, in the hope that both warring families will then forgive them. (The audience has to learn this from the synposis or the play, along with the fact that Romeo fails to be informed of the plan.)

Juliet takes the potion and hides the phial under her pillow. When her parents return with Paris, she appears, reluctantly, to yield to their insistence that she must marry him that day. She makes herself swallow the bitter potion, and crawls in a daze back to her bed. Her bridesmaids come to prepare her for her wedding but find her apparently lifeless. Her nurse and parents are distraught with grief.

Juliet’s body is placed on a bier in the family crypt. Paris stays behind after the mourners leave. Romeo enters the vault to bid farewell to her, unaware that she is not in fact dead. He kills Paris, then lifts Juliet from the bier to embrace her for the last time in an excess of grief. He lays her limp body back on the stone slab and drinks poison he has brought with him. When Juliet awakes to find herself in the crypt, Romeo is newly dead. She finds the dagger with which he killed Paris and stabs herself, trying to reach Romeo’s body as she dies.

The curtain falls on the on the lifeless bodies without the reconciliation of the Montagues and Capulets with which Shakespeare ended his tragedy. The dual suicide has been painful, two young lives needlessly wasted.

Romeo and Juliet’s premiere, with Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev in the leading roles, met with 43 curtain calls; the safety curtain had to be brought down to persuade the audience to leave the theatre. The critical response to the performers and the ballet was fulsome: ‘A spectacular asset to the repertoire . . . altogether a milestone for MacMillan’ (Observer); Kenneth MacMillan takes his place as one of the world’s leading choreographers’ (Daily Mail); Fonteyn’s Juliet was ‘all trust and purity, grace and gentleness, radiance and puppy love’ (Sunday Telegraph). Andrew Porter in The Financial Times was the first to reveal that the role of Juliet was not conceived in Fonteyn’s image: ‘Juliet is plainly a role conceived for Lynn Seymour, and so until we have seen her dance it we cannot be precise about MacMillan’s intentions’.

Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable ©Roy Round

The first performances had gone to Fonteyn and Nureyev because they were a bigger draw than Seymour and Gable. The casting of the famous pair guaranteed a box-office sell out and massive publicity. Sol Hurok, the American impresario, had insisted that if the new ballet were to be included in the Royal Ballet’s next US tour, it must be associated with Nureyev and Fonteyn. Paul Czinner’s 1966 film of Romeo and Juliet featured Fonteyn and Nureyev for the same box-office reasons.

Seymour and Gable danced as the second cast, receiving adulatory reviews for their fresh approach to the roles. They were followed by three other pairings in the first London season and on the US tour in the spring of 1965.

MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet soon became a signature work of the Royal Ballet’s repertoire, and the best known version of the Prokofiev ballet in Britain and the United States. During his lifetime, MacMillan mounted it for the Royal Swedish Ballet in 1971, American Ballet Theatre in 1985 and Birmingham Royal Ballet in 1992 (with new designs by Paul Andrews).

Song of the Earth (Das lied von de erde)

1965

Song of the Earth (Das lied von de erde)

1965

MacMillan created The Song of the Earth soon after Romeo and Juliet, his first three-act ballet. He had long been hoping to choreograph a work to Mahler’s symphonic song cycle, but the Royal Opera House board had rejected his proposal in 1959. When he tried again, after the huge success of Romeo and Juliet, he was told that Mahler was a composer whose music was unsuitable for ballet.

MacMillan offered his idea to the Stuttgart Ballet instead. His old friend John Cranko, director of the company since 1961, had extended an open invitation for him to visit Stuttgart and choreograph whatever he wanted. Cranko agreed to The Song of the Earth as part of a triple bill with MacMillan’s Danses Concertantes and a new work, Opus 1, by Cranko himself. He gave MacMillan first choice of the dancers he wanted to cast.

Since Das Lied von der Erde would be sung in German, the Stuttgart audience would understand the words of the poems Mahler had set to music and see their visual connections in the choreography. The text of the songs is taken from Chinese poems of the eighth century T’ang dynasty, freely translated into German. They are bitter-sweet reflections on human joys, concluding with a farewell to the world: Mahler added four lines to the final verses, ending with the repeated word ‘Ewig’ – ‘Forever’.

MacMillan described the theme of his ballet succinctly: ‘A man and a woman; death takes the man; they both return to her and at the end of the ballet, we find that in death there is the promise of renewal.’ The central couple are part of a group of young people who are blissfully unaware of their own mortality. Among them is a man with a colourless half-mask over his face: he is Der Ewige – the Eternal One. In the English translation he is the Messenger of Death, which lends him a more sinister aspect. MacMillan liked to cast a slight young dancer in the role, apparently no more menacing than his companions, except that he knows what they choose to ignore. (Some interpreters, however, perform the Messenger as though he were Death itself.)

The Messenger shadows the leading man at the start of the ballet, and takes part in the men’s horseplay. He will be present, however briefly, by the end of every song. (MacMillan added him in the fourth song in 1990.) The leading woman appears in the contemplative second song, Autumn Solitude, in which the words reveal her loneliness, her fear of death and her longing for a companion. She is the MacMillan ‘outsider’, sensing that she does not belong to the light-hearted group who amuse themselves during the songs that follow. She finds a lover in a long pas de deux, only to lose him to death. In her final solo, she has to reach an acceptance of her loss, the return of her isolation and the inevitability of death. As she resigns herself to a fate beyond her control, the Messenger returns with the man, who is now wearing a white half-mask symbolising death. All three link hands and step forward together in slow motion, as if into eternity. The curtain falls on their still-pacing figures.

MacMillan’s choreography for The Song of the Earth was different from anything he had devised before. It was his long-considered response to Mahler’s music and the images in the translated Chinese poetry. He introduced orientalisms amid the balletic pointework, asking the dancers to slide flat-footedly, tilt their torsos and bend their arms at the elbows and wrists as if adjusting long flowing sleeves or picking flowers. In the song Of Youth, which describes a porcelain pavilion reflected in a pool, the women kneel demurely as if by water, then later adopt upside-down positions.

Curving calligraphic shapes for the women are contrasted with weightier moves for the roistering men and stark lines and angles in the Farewell pas de deux. MacMillan may have been influenced by Antony Tudor’s expressionist choreography in Dark Elegies, to Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, and by Martha Graham’s modernism. Graham’s work had been seen in London when her company visited in 1954 and 1963, but the Stuttgart dancers on whom Song of the Earth was created had no experience of her technique: for them, MacMillan’s inventions were totally unfamiliar. German dance critics likened the choreography for Das Lied to Viennese Jugendstil or art nouveau, the period in which Mahler was composing his music.

By the time of the premiere, the designs had nothing to do with decorative art nouveau. Georgiadis’s original costumes had been made in chiffon, with floating sleeves. He and MacMillan scrapped them after the dress rehearsal and asked the Stuttgart wardrobe staff to dye simple tunics, T-shirts and tights in bluey-green and purple shades. Der Ewige was in dark grey with a flesh-coloured half-mask. The ballet was given against a plain cyclorama, its colour changing through blues to pale green-yellow.

Royal Opera House board members who had objected to a ballet to Mahler’s music gave in after critics who had seen Das Lied in Stuttgart wrote glowing reviews, urging the Royal Ballet to acquire it. The Royal Ballet first performed it in May 1966, with Marcia Haydée as a guest, Donald MacLeary as the man and Anthony Dowell as the Messenger of Death. Georgiadis changed the colour scheme to monochrome: the cyclorama varies from grey to black, the cast are dressed in shades of grey, the leading woman in white, the Messenger in black. The Stuttgart Ballet retains the original designs and has been performing Das Lied von der Erde, along with MacMillan’s Requiem, in a programme celebrating what would have been the choreographer’s 80th birthday.

Albertine

1966

Albertine

1966

Zodiac was a twelve part series broadcast by BBC1 in 1966 in which dance episodes, both ballet and contemporary, were used to illustrate the various signs of the Zodiac. The producer/director was Margaret Dale, onetime member of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet.

‘Taurus’ was the theme of the edition of 13 May, which included a short ballet by Kenneth MacMillan with Lynn Seymour and Desmond Doyle. This was Albertine, a dramatisation of a story by Barbey d’Aurevilly: a soldier lodges in a house where the daughter makes advances to him. They have an affair. At the end she falls dead at his feet.

(This is clearly the same ballet which Peter Wright remembers asThe Crimson Curtain).

Fernau Hall, reviewed the performance for Ballet Today.

“Both Lynn Seymour and Desmond Doyle were perfectly cast and acted with style and intensity. The crunch came in the bedroom scene, when they launched themselves into a pas de deux in MacMillan’s neo-classical style (very much as in The Invitation): this clashed rather brutally with the extreme naturalism of the acting up to then, and shattered the illusion. The contrast with the corresponding erotic scene in the garden in The Invitation was very instructive: what worked on stage did not work on television, which has its own laws. Nevertheless the work as a whole was intelligently staged and never failed to grip one’s attention.”