The first time I saw Kenneth off the stage was in the ridiculously tiny ballet room at the old Sadler's Wells Theatre. I was in the Opera Ballet and the resident company was, thrillingly, back in London and sharing the theatre with us.

Suddenly a great wrinkled, woolly, purple leg shot into the air amongst the monochrome uniformity of its neighbours. It was shod with a shoe that was definitely on its last legs. It belonged to Kenneth.

As a dancer, Kenneth stuck out for he was extremely tall and loose limbed, gangly even. He had a long, highly expressive face, lachrymose and comic. In repose he adopted an undancerly slouch with his body ever eager to occupy a chair to which he would mould himself like water. But in profile he was a sepulchral poet, with a long nose, dark brows and soulful, deep brown eyes.

“Highly individual, expressive, colourful, unique," I thought to myself, "I've got to get to know this man.”

Kenneth was a skilful performer and created the sad clown, Moondog, in John Cranko's Lady and the Fool , an hilarious existential artist in Alfred Rodrigues' Cafe des Sports and with a meltingly beautiful line, the Moon in Rodrigues' Blood Wedding . He would later proudly inform me that he had received spontaneous applause for his nimble split jetés as Florestan in The Sleeping Beauty when he danced at Covent Garden.

Kenneth decided to leave the company at Covent Garden because, rather like myself, he was more interested in new creations than in the classics and felt he would better be able to develop his talents in the smaller, more contemporary group. He gave up dancing rather precipitously, due, he said, to overpowering stage fright. I am sure his anxiety must have been intense for his life was a constant battle with one crippling fear or another. I also think he had an idle streak and that the daily rigours of class, rehearsal, performance and the idea of beefing up his lanky limbs rather appalled him. Far better to enter into the creative ebb and flow, let someone else do the sweating and lifting that he so detested and then he could remain all day in the clothes he had put on in the morning, albeit, mourning the disappearance of his lean outline as time went on.

Within the touring group in the 1950s Kenneth MacMillan was a sort of buzzword, an in name, discussed in hushed tones close to reverential. There was an air of mystique about him and his work. He was regarded as cutting edge, contemporary; daringly dealing with subjects and issues that ballet had not hitherto addressed. He was offbeat, irreverent, intelligent, great fun and driven to delve and take risks. He was also causing a stir among the critics.

“To the old hands in the company he was a leading light who had developed in their midst.”

To the old hands in the company he was a leading light who had developed in their midst. He had the gift of revealing each individual's talents and had won their respect and belief in his work. To be in one of his ballets, even at the humblest level, was seen as a special bestowal of regard and made you one of a select, elite chosen few.

His Solitaire , based on the outsider Frankie in Carson McCullers' Member of the Wedding , used a romantic score by Malcolm Arnold and pretty costumes by Desmond Heeley who also devised a distinctive new shape for the tutu. Both these attractive accoutrements somewhat disguised the central issue of this piece which was essentially about the excruciating pain of not belonging. Alienation and the search for identity were to be recurring motifs in many of Kenneth's future ballets and they would become far less palliative.

Stravinsky's Danses Concertantes interpreted by Kenneth was originally a chic, sophisticated, mystery cocktail, stunningly set in the dark, jewel colours of Nicholas Georgiadis' lush, provocative and witty world. It was an ambience for uncertain goings-on. Was it a bordello, or some new underground with unwritten rules?

House of Birds was a grim tale of maidens imprisoned as caged birds by a terrifyingly, ruthless female villain. This piece and Danses Concertantes were made vividly visually innovative by the collaboration with Georgiadis whose unerring eye and empathetic understanding of Kenneth's vision emphasised every nuance and direction the choreography was taking. These three works were firm favourites in The Sadler's Wells Touring Company's repertoire during the 1950s and 60s.

The Burrow , Kenneth's study of Anne Frank's world, was where innocent love dared to awaken in the midst of oppression, hysteria, and terrifying claustrophobia. He was extremely collaborative and encouraged us to read the diaries and other pertinent literature, to imbue ourselves with the study of fear and of human relationships where privacy was denied.

He was at pains to remove cliché from the balletic vocabulary and to approach the familiar from an oblique angle. He used the idiosyncrasies of individual bodies and each dancer's personal qualities to build complex, veritable characters and welcomed any ideas and input from the cast. We all took our characters home with us, studying people in the streets and cafes for clues, reading volumes and scouring galleries and museums where ever we went. We discussed it endlessly. This was when I knew that the creation of new works was my raison d’être.

The Invitation is another early, dark study that peels away the veneer of social decorum to reveal the raw reality and terrible abuse that exists in real life. It was originally conceived as a two-act piece. After the tragic and untimely death of the composer, Matyas Seiber, it had to be honed to only one act. Madam was very concerned about the rape scene and wanted it to take place offstage! To her credit and Kenneth's relief, she did not insist.

Kenneth made each dancer an integral part of the creative process, encouraging and stimulating the imagination to the limits, searching the soul for verity, no false airs and graces, no sentimentality, no pasted-on emotions. He wanted raw, gutsy, unattractive humanity out of which true aspects of the human condition could emerge. This kind of psychological delving and digging was not common practice in the ballet world of those days. With Kenneth we all felt like privileged scientists, pioneers opening hitherto unexplored territory and at the very forefront of innovation.

Kenneth also brought sex into the frame. In his Danses Concertantes , he had entered these murky regions producing a sleek, cryptic work laden with sexual portent and, alluded to more than met the eye. In The Burrow , each character was provoked by either sexually motivated neurosis or impulse, none of which could remain hidden because of their imposed, suffocating proximity to one another. Their deepest secrets and shame were ultimately exposed to scrutiny and judgement. The Invitation used an explicit rape to define not only sexual abuse but as a metaphor for the abuse of power in all its connotations.

“Of course, sex and psychology were in the air. The French nouvelle vague was about to wash over us.”

Sex in the rehearsal room was new. Candid sexual discussion was new. Kenneth used it to tease and provoke, to stir the dancers' awareness of their own sexuality and to that of others. Of course, sex and psychology were in the air. The French nouvelle vague was about to wash over us. Osborne, Pinter, Stoppard, Bond and Ionescu were waiting in the wings and Joan Littlewood was on the verge of giving us Realism with a capital "R" and further rocking the boat by unleashing the irreverent poet, Brendan Behan, on an unsuspecting conservative Britain.

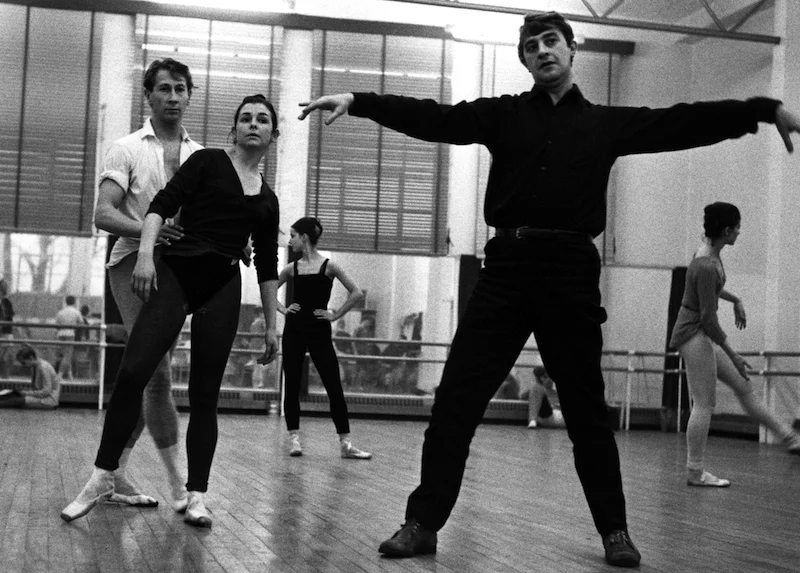

Desmond Doyle, Lynn Seymour and Kenneth MacMillan rehearsing The Invitation 1960 ©Roy Round

Kenneth ushered this Zeitgeist into the world of British Ballet. There was little of the pedagogue or ballet master in Kenneth; in fact he always seemed impatient with the necessity of maintaining regular attendance at class, eating properly or getting enough sleep. He did tell you where you were lacking and found it difficult to wait whilst you developed the necessary expertise or knowledge. In fact his impatience usually resulted in him irritably changing a step that was proving elusive in order that something pleasing was arrived at straight away and his vision was instantly fulfilled.

Kenneth made me acutely aware of stagecraft. "You have to know where all the lights are on the stage at any given time and use them to highlight the effect you wish to achieve/' I would gaze helplessly at the banks of lights above and surrounding the stage and wonder how one could accomplish such precise placement at the same time as tangling with the intricacies of dancing. He stressed how timing and stillness could have the same effect as the zoomed-in close-up in film, an art form that had always influenced him. He would stress how a fingertip or tiniest turn of the head could denote volumes. Of course, it was up to me to find out how to achieve these skills and we had the good fortune to perform eight times a week, experimenting constantly.

Later, I would join the ranks of Kenneth's friends. Our duty was to provide him with the entertainment and moral support he constantly needed in return for his trust and wicked schoolboy humour. He was once rather aptly described as a "rumpled rajah". He always seemed to have dressed in haste or absent-mindedly, yet was somehow touchingly vain about his appearance. He fretted about it but seemed incapable of taking decisive or regular action in that regard. Instead he would melt into the most comfortable chair with the languor of an odalisque and preside over the meeting demanding to be entertained, to be stimulated, and to be informed of the latest gossip, most especially of the more salacious variety. In short, food and fodder for his next creation.

Despite our friendship and the regular, almost ritualistic meetings there was a part of Kenneth that was always remote, unknowable, and inaccessible. It was in the rehearsal room that Kenneth and I were, somehow, mystically unified. Something clicked and I seemed to be able to sense his direction without a word being spoken; I would try anything he suggested without question. Awkward juxtaposition of limbs, back-to-front combinations of steps, inside out ports de bras, tap steps, acrobatics, anything at all. I could use my old tap-dancing skill to break down steps into complex rhythms or swoop into Hollywood style beguines.

“Kenneth risked ignoring the aesthetic standards of symmetry that preceded him in Ashton by seeking the effect of randomness, whilst still trying to satisfy the sophisticated eye.”

Kenneth risked ignoring the aesthetic standards of symmetry that preceded him in Ashton by seeking the effect of randomness, whilst still trying to satisfy the sophisticated eye. In Le Baiser de la fée and act two of Anastasia , for example, he doffed a cap to Petipa's symmetry in order to denote period and musical references whilst interweaving twentieth century innovation within its structure. On the whole he seemed to seek the haphazard groupings of flocks of birds or more human social gatherings. Unusually, the floor patterns or flight paths of pas de deux and solos were usually only arrived at after a passage of dance had been created.

I do not think Kenneth wanted to pin down these shapes and forms too rigidly fearing the veneer of artifice, or the loss of authenticity that would remove the truth from that which he was trying to express. He loved the immediacy of the serendipitous accident and was constantly reiterating the refrain, "Let's see what happens if..." I think that this reluctance to define the form makes his work uniquely difficult to recreate. In addition, much of what he wanted, or pleased him, was in his mind's eye and he had great difficulty expressing exactly what it was that he was seeking to arrive at or depict. However, a great many of his choreographic patterns were not random, although it may have appeared so and, as in any other work, if his eccentric and vaguely defined flight paths are not understood or adhered to, the dynamic and intent of his work is cruelly undermined.

Ultimately, Kenneth was reared in Ashton's Apollonian court but was fascinated by the opposing realm of Dionysus. Entranced and influenced by Hollywood’s conflicting images of Puritanism, sex and romance he was also obsessed with cruel passion and corruption and Freud's dangerous, capricious and innately sexual id .

“He began, like Ashton, writing his ballets in the feminine first person, expressing his own feelings of alienation and sexual confusion in feminine form.”

He began, like Ashton, writing his ballets in the feminine first person, expressing his own feelings of alienation and sexual confusion in feminine form. No chic, sophisticated veneers, but purposely awkward, often ugly movements to denote realism. Dying in fifth position was a ridiculous abomination to him and he often worried about the artifice of the pointe shoe. A naked foot or high heeled shoe would be more truthful but this conflicted with the extra mobility the pointe shoe would allow. Conflict, always conflict.

Lynn Seymour, David Wall, Kenneth MacMillan in rehearsal for Mayerling 1978 ©Roy Round

Kenneth was a voyeur, a provocateur luring his dancers into the seamy side of life and proposing dark identities, and pathological, neurotic motivations whilst trying not to get his own feet wet. After his first terrifying episode of both physical and mental ill health his course altered. This was reflected in his choreography where his first person became masculine. His heroes became ultra masculine, often cruel and misogynistic, often tragic. These men were frequently used, betrayed, abused in love, misunderstood and tainted by overbearing, uncaring, greedy women who were universally flawed and physically manipulated. Women were no longer representatives of his innermost feelings. They were portrayed as morally weak or corrupt, and were fair game for abuse and humiliation. He threw his characters into the seething sexual waters of the Dionysian kingdom whilst he loftily perched at the side of Apollo and in the romantic tradition took up the pen of the Marquis de Sade looking on at their convolutions at a safe remove.

Lynn Seymour was a principal dancer with The Roval Ballet, prima ballerina at Berlin Opera Ballet and has guested with many other companies. MacMillan created a number of leading roles for her which established her as a leading dance-actress of her generation. She has choreographed several works and was also artistic director of Munich State Opera Ballet.