1953 - 1960

1953 - 1960

Somnambulism 1953

Fragment 1953

Punch and the Child 1953

Laiderette 1954

Danses Concertantes 1955

House of Birds 1955

Turned Out Proud 1955

Tannhäuser 1955

Noctambules 1956

Solitaire 1956

Fireworks 1956

Valse Excentrique 1956

Winter’s Eve 1957

Journey 1957

The Burrow 1958

The World of Paul Slickey 1959

Agon 1959

Expresso Bongo 1959

Somnambulism

1953

Somnambulism

1953

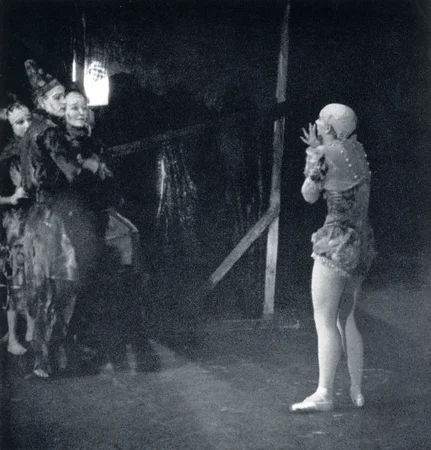

MacMillan’s first ballet Somnambulism revealed a precocious young talent. The anxieties it explored were rooted in MacMillan’s own; he would return to these anxieties and elaborate them in many of his subsequent works. Made in a week to fill a gap at a choreographic workshop, Somnambulism was the success of the evening. It was set to three jazz pieces by Stan Kenton, rearranged by the conductor John Lanchbery.

Somnambulism’s three main characters, were portrayed as if in dreaming sleep, variously troubled by anxiety, monotony and premonition. A corps de ballet of six wore black masks to transform them into the faceless fantasies of the three dreamers.

MacMillan created the leading female role for Maryon Lane, and he himself performed as one of the two men. This was a late change: because Margaret Hill, the intended dancer, was ill on the day, MacMillan adapted her steps for himself, making impromptu improvisations. Lane, who danced Premonition, was menaced by gloved hands reaching out from the wings. When she grabbed at a hand, a body fell dead at her feet. She believed herself responsible for the man’s death, watching in horror as his corpse was carried across the stage in a mock funeral procession. In the solo representing Monotony, David Poole danced the same step over and over, “a study of a young man rocked by conflicting emotions, as if in a brainstorm, being mentally tortured” (Dance and Dancers).

Somnambulism (1956), Photo: Denis De Marney. Image courtesy Victoria & Albert Museum (www.vam.ac.uk)

Lane recalled that the ballet was prepared in a small room at Sadler's Wells Theatre so cluttered with skips and wardrobe baskets that the floor space was barely eight feet square. For the workshop presentations, De Valois had stipulated that sets and costumes were to be kept simple. Somnambulism’s cast wore practice dress, their only props black masks and white gloves.

For the dance writer Peter Brinson, Somnambulism was “clear-cut, precise, highly original in construction and very demanding on the dancers”. Clive Barnes thought it “obviously the work of a new choreographer potentially of the first rank”’. As The Dreamers, it was subsequently performed live on BBC TV, with the score played by the Ted Heath Orchestra. In 1956 it was briefly taken into the repertory of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet.

In March 1953, the magazine Dance and Dancers featured MacMillan as its Personality of the Month and applauded his talent. “His remarkable invention of movement, understanding of mood, sense of theatre and how to use a stage, make this one of the most mature first works we have seen”. With this success behind him, MacMillan joined his friend John Cranko as a choreographer for Sadler's Wells Theatre Ballet and for Covent Garden. Within a short time, British ballet, still in its nascent state, had produced two choreographers who would prove to be major artists.

First performance: Sadler’s Wells, London, 1 February 1953

Company: Sadler’s Wells Choreographic Group

Cast: Maryon Lane, David Poole, Kenneth MacMillan

Music: Stan Kenton (arranged John Lanchbery)

Fragment

1953

Fragment

1953

This was MacMillan’s second workshop piece and it was performed along with Somnambulism, his success of several months previously. In idiom the two pieces were similar and again MacMillan used music by Stan Kenton. Like Somnambulism, the piece was made in a hurry. According to Edward Thorpe, MacMillan had hoped to use Gershwin’s Piano Concert in F, but had to settle for Kenton as he had little time to prepare.

While Dance and Dancers recorded the ‘incredible verve’ of Britton’s dancing and Annette Page’s ‘especial brand of humour’, its critic was underwhelmed. “The whole thing seemed like a tiny chip of the old block. We may have to wait a bit longer before we know if MacMillan is really the promising young choreographer we believe him to be.”

First Performance: 14 June 1953

Company: Sadler's Wells Theatre

Music: Stan Kenton

Cast: Sara Neil, Donald Britton, Annette Page

Punch and the Child

1954

Punch and the Child

1954

The BBC children’s programmes department gave Kenneth MacMillan his first opportunity to choreograph for television. The three episodes of Steps into Ballet were broadcast from the Lime Grove studios in West London and produced by Naomi Capron. An educational series, devised as an introduction to ballet steps, it included story inserts about a young girl determined to see a Punch and Judy show at the seaside. When she visits Punch’s booth, against her parents’ wishes, she is caught up in an unexpected adventure with a character called Pretty Polly and a policeman played by Kenneth MacMillan himself.

In the early years of television most programmes were live. Only a few were telerecorded. A telerecording consisted of placing a film camera in front of a monitor and recording the pictures displayed by the monitor on to film. This was the method used until the arrival of videotape.

No recording exists of Punch and the Child.

Laiderette

1954

Laiderette

1954

Laiderette (from the French ‘laideronette’, “little ugly one”) like Somnambulism was a workshop production for the Sadler’s Wells Choreographic Group. Its motifs of rejection and exclusion would be recurrent themes in MacMillan’s later work. Maryon Lane danced the lead role, a Pierrot-like heroine; a young girl whose admirer rejects her when her bald head is revealed.

The heroine is one of a troupe of itinerant clowns, who abandon her outside a great house where a masked ball is under way. A mask-seller places a mask over the sleeping girl’s face. One of the male guests discovers her and goes inside to tell the others. The host invites the mysterious stranger to join the party. They dance with abandon, but when the time for un-masking comes, her cap comes off as well and her baldness is revealed. Mocked and reviled, she is mournfully reclaimed by her clown family. They hold up a mirror and she sees herself as she truly is. She runs back up the steps to the house, where the host rejects her once again. He returns to the gaiety of the ball and Laiderette is left sobbing as the curtain falls.

Laiderette 1954

The choreography for the heroine, danced by Maryon Lane, was intricate and strange. She moved at first with the gaucheness of a child, swivelling her knees sideways, turning her toes in and out, beating her flexed feet together then arching them in quick relevés on pointe. In her signature step, a flowing arabesque was distorted into an angular attitude position for the raised leg. Her arms were held behind her, hands clenched or splayed out in anguish. Lane later said that she recognised the character as a projection of MacMillan, scared that the world would reject him if people knew what he was really like.

The Frank Martin music, requiring solo harpsichord and harp, made the ballet expensive to perform and difficult to fit into a touring programme; and the Musicians’ Union would not agree to the use of recorded music. But de Valois was impressed enough to offer MacMillan his first full commission for Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet, Danses Concertantes (1955). Marie Rambert acquired Laiderette for Ballet Rambert, which gave it a full stage production at Sadler’s Wells in July 1955, with designs by Kenneth Rowell. It remained in Rambert’s repertory until 1967.

‘Here was a work of near-genius’, declared Peter Williams in Dance and Dancers. ‘If this and his first work, Somnambulism, are fair examples of what we can expect from MacMillan, we have a choreographer of major dimensions’.

First Performance: 24 January 1954

Company: Sadler's Wells Theatre

Music: Frank Martin

Cast: Maryon Lane, David Poole

Design: Kenneth Rowell

Danses Concertantes

1955

Danses Concertantes

1955

Danses Concertantes was MacMillan’s first major work: his first for the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet; his first Stravinsky ballet (seven others would follow); and his first to be designed by Nicholas Georgiadis, still a student at the Slade School. Arnold Haskell hailed the emergence of “a genuine choreographer of a rare kind”. Encouraged by the response of audiences and critics, MacMillan decided to stop dancing and to commit himself wholeheartedly to choreography.

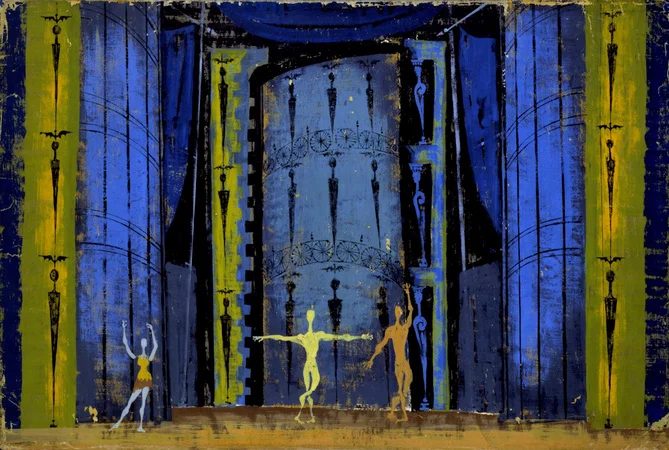

Danses Concertantes (1955), set design Nicolas Georgiadis.

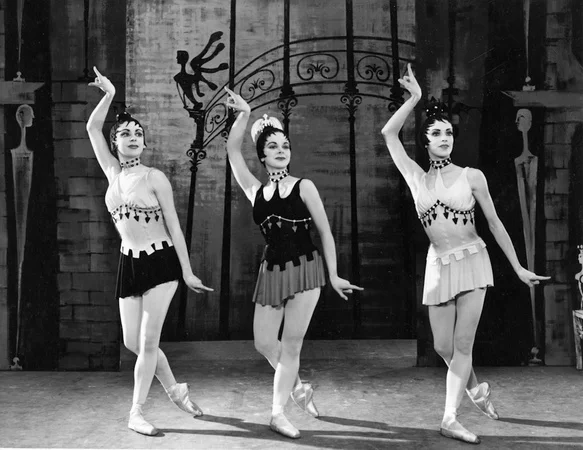

Danses Concertantes (1955), Annette Page, Marion Lane and Sara Neil. Photo: Denis de Marney. Image © Victoria & Albert Museum (www.vam.ac.uk)

Although Stravinsky's score is for concert performance by a chamber orchestra, his chosen title also made clear his ambition for a dance staging and Balanchine had already choreographed his version in 1944. For Balanchine the score suggested the spirit of the commedia dell’arte; MacMillan was similarly drawn to the music’s “humorous and witty” quality and its suggestions of “a kaleidoscope of ever changing patterns”.

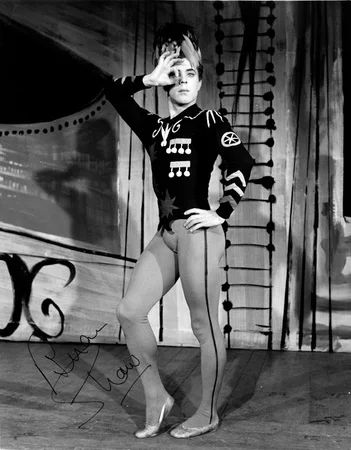

Danses Concertantes (1955). Photo: Houston Rogers. Image © Victoria & Albert Museum (www.vam.ac.uk)

Danses Concertantes is a plotless ballet where sharpness is all. The choreography consists of an intricate suite of dances. There is a bustling general dance full of entrances and exits for the company, a pas de trois, a rumbustious solo for a male dancer, an adagio for the ballerina and five cavaliers, and a pas de deux. MacMillan responded to Stravinsky’s acerbic chamber score with sharp spiky choreography; pointing fingers, jarringly broken line, angled ports de bras and sudden swift turns in direction. Danses Concertantes was fast, fleet and contemporary with hints of jive, revue, cinema and the circus. Georgiadis’s hectic colours (lime, orange, electric blue) strongly recalled the Festival of Britain. His nervy lines of decoration, his fantastical mix of jazz and carnival references (echoing the score) similarly spoke of a generation breaking free of 1950s restraint.

Next morning, The Times praised Macmillan for choreography which “could hardly be bettered” in its realisation of the music and for invention that was “happy, copious and unforced. The orchestra laboured with the broken-backed rhythms but the dancers had them pat”.

Clement Crisp was also in the first night audience. “I still recall how the eye was teased by the sparks of energy and wild originality given off by the movement, how the Georgiadis designs glowed and flashed, how bright-footed the young cast seemed. Why had no-one ever used fingers like this before? Or turned staid ideas on their heads, and made partnering witty? Danses was a declaration of talent, of the arrival of the new heir.”

First Performance: 18 January 1955

Company: Sadler's Wells Theatre

Music: Igor Stravinsky

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast: Maryon Lane, David Poole, Donald Britton

House of Birds

1955

House of Birds

1955

John Cranko suggested the theme for MacMillan’s third ballet, House of Birds, based on the Grimm Brother’s macabre fairy tale, Jorinda and Joringel. A witch, The Bird Woman, snares young children and transforms them into birds. When the witch is overcome by two true lovers, the spell is broken; the witch’s victims peck her to death and resume human form. While the turning of mortals into birds is a familiar pastime of ballet sorcerers, House of Birds was one of only three MacMillan ballets which drew for inspiration on fairy tales (The other two are Le Baiser de la fée and The Prince of the Pagodas).

Arnold Haskell found in the first night performance “something of the thrill of a Diaghileff première” while the ballet impressed Clive Barnes of Dance and Dancers for its “brilliance and its oddness”, which would “assuredly earn MacMillan a one way ticket to Parnassus or Bedlam.” The Times found “much to intrigue the eye, but much that is fundamentally repellent.”

House of Birds 1955

This was MacMillan’s second collaboration with Nicholas Georgiadis; for several critics there were influences of Paul Klee. The Guardian thought the designs “strange, piquant and right”. For the traditionally anonymous reviewer from The Times the designs were the ballet’s most striking elements, “brightly coloured but impregnated with cruelty, nature red in tooth and claw. From the outside of the Bird Woman’s aviary we see the facade and, as it were, an X-ray plan of the interior; and the analytic method is repeated in the Bird Woman’s macabre costume” (black tights on which Georgiadis painted a birdly skeleton).

The choreography for the Bird Woman (Doreen Tempest) suggested automaton movement and the complete absence of emotion (for Clive Barnes, “the personification of evil down to the last baleful feather”). The witch wore a heavy beak, her victims’ heads were held in birdcages. Although this complicated the movement possibilities, it also made for choreography that was ugly, jerky and full of menace.

Maryon Lane danced the girl transformed into a bird and then rescued by her lover (David Poole). For Barnes a pas de deux between the couple (complicated lifts foreshadowing future MacMillan couplings) inevitably echoed that in Fokine’s The Firebird between the Firebird and Ivan Tsarevitch.

Costume designs for House of Birds ©Nicholas Georgiadis

John Lanchbery suggested to MacMillan that he use music by the Catalan composer Federico Mompou. "I was mad about Mompou, who was little known in England at the time. I bought everything of his I could find and put the score together. Kenneth came and I played it through, and we did it there and then. Just like that."

First Performance: 26 May 1955

Company: Sadler's Wells Theatre

Music: Frederic Mompou arr. John Lanchberry

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast: Maryon Lane, David Poole, Doreen Tempest

Turned out Proud

1955

Turned out Proud

1955

Turned Out Proud was a BBC commission shown in the Music at Ten series and was MacMillan’s third television work after Punch and the Child and The Dreamers, an adaptation for television of Somnambulism. Broadcast live from the former Lime Grove studios in Shepherd’s Bush, London, it was Margaret Dale’s first project for the BBC. A former dancer with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, Dale in years to come adapted and directed much of The Royal Ballet’s work for television.

Turned Out Proud 1955

Turned Out Proud was a danced revue in nine parts, introduced by an opera-cloaked impresario (actor John Neville of the Old Vic). The dancers came from the two Sadler’s Wells companies, along with one star guest, Violette Verdy. According to Dance and Dancers, a pas de deux for Verdy and Gilbert Vernon was ‘the highlight of the evening’. There was also a 1920s pastiche for Julia Farron, who, dancing in a park, tried to distract four boys from reading their newspapers. “The programme closed”, Dance and Dancers recorded, “with a rousing blues of those terrible twenties and the days of New Orleans jazz. Verdy, brandishing a long cigarette-holder, might almost have wandered in from I am a Camera”.

The music was chosen less for its innate quality than for the fact that it did not attract copyright fees. Critical reaction was mostly warm; The Stage declared it “an experiment to be encouraged”; Dance and Dancers praised MacMillan’s unceasing invention, while Mary Clarke, writing in the Ballet Annual thought it “the liveliest half hour of television dancing for a long time.”

First performance: 23 October 1955

BBC TV dir Margaret Dale

Cast: John Neville, Violette Verdy, Julia Farron, Gilbert Vernon, Sonya Hana, Sheila O'Neill, John Stevens

Tannhåuser (venusberg)

1955

Tannhåuser (venusberg)

1955

This was Kenneth MacMillan’s first commission for Covent Garden, which at the time maintained a small Opera Ballet of twelve dancers separate from the main ballet company. The Venusberg ballet comes in act one of Tannhäuser and represents the sensual world of Venus and her realm, with which the opera’s protagonist is helplessly enchanted. It was not part of Wagner’s 1845 original; he introduced the scene at the behest of the Paris Opera in 1861, where the insertion of a ballet in the score was a house tradition.

The 1955 Covent Garden production was not a success. The Observer called it “a ludicrous misalliance between Ralph Koltai’s expressionistic sets and a singularly ill-executed production by Sumner Austin.” Only MacMillan’s choreography won praise. For The Times the bacchanale in the Venusberg was “better than is usually contrived”. For Dance and Dancers, “MacMillan almost alone did nothing to detract from his growing reputation”. While the erotic by-play of the choreography had “more kinship with Petit than Fokine”, a more conventional romantic bacchanale “would have been out of place in Ralph Koltai’s starkly chic settings”.

However, the popular press was now taking notice of MacMillan. “Has the Lord Chamberlain seen it?” asked The Daily Mail. “The astonishing Bacchanal dance sequence in the new production of Tannhäuser at Covent Garden is the talk of the town. It shows scantily dressed bacchantes, sirens, naiads and nymphs in poses that, in my opinion, would be banned from the Folies Bergère. “It’s not all that erotic. MacMillan said. “In fact, I thought it rather tame.…” I don’t know what Mr. MacMillan considers suggestive. But the fact remains that the Covent Garden administrators will not let the scene be photographed – at any price.”

First Performed: 21 November 1955

Company: The Royal Opera, The Royal Opera House

Music: Richard Wagner

Design: Ralph Koltai

Cast: Julia Farron, Gilbert Vernon

Noctambules

1956

Noctambules

1956

Noctambules was of a different scale to MacMillan’s previous ballets. It was his first work for the main company on the Covent Garden stage and his first to a commissioned score.

In MacMillan’s scenario, a vengeful hypnotist hypnotises the audience in a small theatre after they scoff at his act. Under hypnosis a soldier becomes a hero, a couple fall in love, a faded beauty regains her charms and wins four suitors. The hypnotist, discards his stage assistant for the beauty he has created, but she, waking from her dream, recoils from him. At the premiere, Leslie Edwards was the hypnotist with Nadia Nerina as the Faded Beauty, Desmond Doyle as the Rich Man, Anya Linden as the Poor Girl, Brian Shaw as the Soldier and Maryon Lane as the Hypnotist’s Assistant.

Noctambules (1956). Photo: Michael Dunne. Photo supplied courtesy of the Music Library, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

For Mary Clarke, writing in Ballet Annual, “there was never a trace of the tiro in a work that was completely consistent”, but the scenario fell short with a sense that “strange happenings under hypnosis weren’t strange enough.” Alexander Bland of The Observer thought the ballet fell short – and for this he blamed Georgiadis’s designs. “He has attempted, fatally, to combine mystery and drama with a kind of feverish gaiety. How can one take seriously a pantomime Svengali in black, green and lilac; or a rich lover whose velvet is sprinkled with drop pendants: or a soldier who mows down his friends in a crazy tommy-gun dream – but decked in purple cock’s plumes? This is not drama but melodrama – Grand Guignol at the Chelsea Arts Ball. All the same a real imagination is cooking away there somewhere. When the fitful fever has died down, MacMillan may well produce something to astonish us.”

But Clive Barnes, writing for Dance and Dancers, was contemptuous of older critics’ dismissal of Noctambules as ‘melodramatic’. “The choreography, which owes something possibly to MacMillan’s very first ballet Somnambulism, is often shockingly original. It has something of Ashton in it (the pas de deux and grand adagio, for example, have certain Ashtonian characteristics) but MacMillan’s style is remarkably individual. He is to Ashton what Robbins is to Balanchine; two formidable and self-willed apprentices for two formidable and self-willed sorcerers.”

The Manchester Guardian’s critic JHM (possibly James Monahan) praised “an extremely good work, rich in well-made dances.” But for The Times’ un-named critic, “every effect did not tell perfectly in the first performance: what pleased the audience was a ballet with aspirations but not pretentiousness and a ballet that effectively brings out the qualities of some of the younger dancers in the company.” A group from Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, in London to discuss possible exchange visits between the two companies, was, The Times reported a few days later, “enthusiastic about Noctambules, whose choreography, decor, and music lie far outside the experience of the Bolshoi repertoire”

This was also the first time MacMillan had choreographed to an original score, not a completely happy experience. De Valois had suggested Humphrey Searle, to whom MacMillan gave a very detailed scenario. When the piano score arrived, it was patently too long, but the young MacMillan was too diffident to ask for cuts. Mary Clarke remarked that it was “admirable in suggesting the atmosphere, but less successful in developing the narrative.” For The Manchester Guardian’s JHM the score seemed “altogether too apocalyptic: the drumming and discordancies belong not to a charlatan’s theatrical mystifications but to the day of judgement.”

First Performed: 1 March 1956

Company: Sadler's Wells Ballet

Music: Humphrey Searle

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast: Leslie Edwards, Maryon Lane, Nadia Nerina

Solitaire

1956

Solitaire

1956

Solitaire (1956), tutu worn by Patricia Ruanne as The Girl. Image courtesy Royal Opera House Collections (www.rohcollections.org.uk)

Kenneth MacMillan made Solitaire in response to a request by Ninette de Valois for a new work to substitute for a John Cranko ballet (The Angels) which had had to be postponed. Designs by Desmond Heely had already been commissioned for the Cranko ballet and MacMillan was asked to use them.

Solitaire (1956). Photo © Leslie E. Spatt.

MacMillan subtitled his new work ‘A kind of game for one’; he also described it as a “a divertissement ballet”. Which in essence is what it was; a sequence of dances knit together by Malcolm Arnold’s Eight English Dances and by the continuity provided by Margaret Hill’s appearance in each one. “It is this girl”, wrote JHM of The Guardian, “who provides the only obvious choreographic thread, now as soloist, now as partner in a choral dance, now merely an observer of the rest of the cast: they, it seems, are her playthings.” This figure is a leitmotif in MacMillan’s work: she is an outsider, an observer; she tries to join in but is always in the end alone. The other characters may exist only in her imagination

The Times critic (un-named but possibly Clive Barnes) remarked that MacMillan’s eye for theatrical effect owed something to Ronald Petit, but that “he is more musical than Petit and, since his choreographic invention is stronger, he has less need to rely on dramatic assault”. “The choreography takes a hint or two from English country dances”, The Times continued,, and “it is never a romp; it pick up ideas from the composer’s keen instrumental colour-sense and it does not go on too long.”

For The Observer’s Alexander Bland, Margaret Hill was ‘too positive a character’ to convey the ambiguity of the girl, half-in, half-out of the goings on around her. “In the beautiful pas de deux she was excellent, but it’s no point her pretending to be Alice in Wonderland”

The night of the ballet’s premiere was the first time that an entire evening had been devoted to the work of a choreographer from the emerging generation; the other ballets performed in the programme were Somnambulism, Danses Concertantes and House of Birds.

First Performed: 7 June 1956

Company: Sadler's Wells Theatre Ballet

Music: Malcolm Arnold

Design: Desmond Heeley

Cast: Margaret Hill, Donald MacLeary, Sara Neil

Fireworks

1956

Fireworks

1956

In Summer 1956 Nadia Nerina and Alexis Rassine toured the English regions with their Ballet Highlights programme consisting mostly of various pas de deux. Early performances were indifferently reviewed by some critics; The Manchester Guardian complained that the pas de deux lacked impact torn, as they were, from context and anthologised.

MacMillan created a bravura pas de deux, Fireworks, which received its first performance in Oxford, later in the tour. It seems to have had the necessary effect. For Dance and Dancers, Fireworks was by far the most interesting part of the programme “rather in the manner of the solos from Noctambules”.

Music: Igor Stravinsky

Cast: Nadia Nerina, Alexis Rassine

Valse Excentrique

1956

Valse Excentrique

1956

MacMillan created Valse Excentrique for a gala given in aid of Hungarian refugees in December 1956. Earlier that year Soviet troops had invaded Hungary and suppressed all public opposition to the country’s hardline Communist regime. Three thousand people died, while two hundred thousand Hungarians fled to the West.

Valse was the single newly-created work performed at the Gala. MacMillan’s chosen music was the Ibert Divertimento written for Eugène Labiche’s play, The Italian Straw Hat. In a slow-motion pas de trois for three Victorian bathers, a girl (Anya Linden) was gently passed between two suitors (Brian Shaw and Alexander Grant, both in Edwardian bathing suits and handlebar moustaches). For Dance and Dancers, Valse had “all the imagination and invention we associate with its choreographer” with Linden producing “a surprising vein of zany comedy as the young lady in not too much distress.” The costumes were suggested by Alexander Grant. They were originally designed for Ashton’s beach ballet Les Sirènes (1946) in which Grant was cast as one of a group of children. The piece was exuberantly received (“louder laughter than has ever been lavished on the Crazy Gang”, according to the 1958 Ballet Review).

Although intended as no more than a pièce d’occasion, Valse Excentrique did have an afterlife. In 1958 MacMillan restaged it for Western Theatre Ballet with designs by Ian Spurling (it formed part of the programme for WTB’s American tour in 1963). It continued to be danced at fund-raising galas into the 1970s (“part of an underground Royal Ballet repertory seen only in this kind of programme”, according to The Times in 1969). It was briefly in the repertory of the Royal Ballet New Group in 1972—’73 clocking up seventeen performances.

First performed: December 10 December 1956

Gala, Sadler's Wells Theatre

Music: Jacques Ibert

Cast: Alexander Grant, Anya Linden, Brian Shaw

Winter's Eve

1957

Winter's Eve

1957

Lucia Chase, the director of American Ballet Theatre, visited Europe in August 1956 in pursuit of new work to broaden her company’s repertory. The critic Peter Williams introduced her to Kenneth MacMillan and shortly afterwards Chase commissioned him to make a ballet for ABT, with Nora Kaye and John Kriza as the two leads.

MacMillan proposed several librettos; Chase was attracted most to a story, vaguely inspired by Truman Capote, of a blind girl who tries to keep her blindness a secret from a young man and eventually renders him blind also, by accident. When they first meet and fall in love, the air is filled with birds which represent her soaring emotions. She accepts his invitation to a ball, during which he realises she is blind. Immediately the birds return. This time they are menacing and angry. The girl strikes at them. In doing so, she accidentally blinds the young man.

MacMillan planned to have a specially written score by the French composer Henri Dutilleux, who had written the score for Roland Petit’s Le Loup (MacMillan later choreographed Métaboles (1978) to music by Dutilleux). But because time was short, a commissioned score was abandoned in favour of Britten’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge.

Designs were by Nicholas Georgiadis; he had hurriedly to rethink them because of Chase’s dislike of mauve, the dominant colour in the ballroom scene. John Martin of The New York Times thought both decor and costumes “sumptuous and handsome” and “also eminently Parisian in quality.” (The set was built and painted in Paris).

The final go-ahead only came in December. Because of the Suez crisis ABT had had to abandon a tour of the Middle East and substitute a European tour. By 31 December 1956 MacMillan had sketched out a ballet for the two principals and a corps of 16. On January 16 1957 the premiere took place in Lisbon, where local press reaction was enthusiastic, even if the critics of both the Diario de Noticias and O Seculo considered the story improbable.

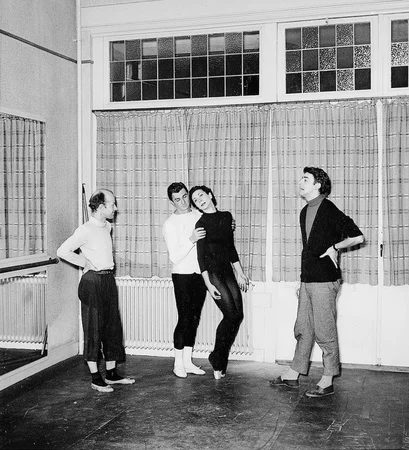

Winter's Eve (1957). Kenneth MacMillan rehearsing Nora Kaye and John Kriza

“Tragic events at a macabre-romantic ball – we are in fairly familiar balletic territory here”, wrote David Vaughan for The Guardian when the ballet had its New York premiere on 10 February. “However”, he continued, "Winter’s Eve is saved from cliché by the sharply individual flavour of MacMillan’s idiom and his compassionate, if detached, attitude to his characters.”

For The New York Times critic John Martin, Winter’s Eve “had everything the matter with it. The work as a whole is callow, cruel, capricious and chichi and yet, there remains the indubitable evidence of Mr MacMillan’s talent. Invention is at present his greatest asset and his greatest danger, for he can turn out an endless amount of original movement without developing any of it. As a result he abandons his principal character about the middle of the piece and leaves her largely to shift for herself thereafter.” Ninette de Valois, Martin suggested, would not have countenanced such a scenario.

However Walter Terry of the New York Herald Tribune was sufficiently enthused to devote two lengthy reviews to MacMillan’s ballet. Like Martin he agreed that the ballet had flaws; however he thought that MacMillan had extended ballet vocabulary into a freer form of expression and emotional revelation.

First Performed: 16 January 1957

Company: American Ballet Theatre

Music: Benjamin Britten

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast: Nora Kaye, John Kriza

Journey

1957

Journey

1957

In May 1957 American Ballet Theatre presented fifteen new ballets by young choreographers over four consecutive Mondays in the off-Broadway Phoenix Theater. Dance writers were invited to view the ballets as ‘laboratory productions’; most were presented without sets and with simple costumes.

MacMillan’s Journey featured four principals, three soloists and an ensemble of three women and twelve men. Its subject was death, from the first premonition of it to the final judgement, and was in four sections – Premonitions, Three Messengers of Death, Journey and Judgement. The men, used in the manner of a Greek chorus, come somersaulting from the wings at the outset.

Journey (1957) Nora Kaye in The American Ballet Theatre production

Arthur Todd, writing for Dance and Dancers, remarked on a work “replete with some of the most inventive and unusual dance movements seen in a ballet in several seasons in New York.” In September 1958, ABT included Journey in a programme at the Metropolitan Opera House. John Martin of The New York Times was considerably more impressed than he had been with Winter’s Eve, MacMillan’s previous commission for the company. “It is certainly not one for the balletomanes, but it is an original and a stunning work.”

Martin continued: “The choreography is a marvel of invention, the kind of intuitive invention that is generally associated with the modern dance rather than the ballet. The massed chorus is used with power and variety, and the individual figure of Miss Kaye stands out in high relief against it. In the second section she unwittingly goes out jazzing, as it were with three red-clad angels of death and only at the end of the scene does she realise who they are and what has happened. It is a remarkably macabre and beautifully conceived scene and it is remarkably danced.”

First performed: 6 May 1957

Company: American Ballet Theatre

Music: Béla Bartók

Cast: Nora Kaye, John Kriza, Erik Bruhn, Scott Douglas

The Burrow

1958

The Burrow

1958

To its early audiences for whom World War II was a recent memory, Kenneth MacMillan’s psychological drama The Burrow strongly recalled the harrowing Diaries of Ann Frank. In his depiction of human suffering, MacMillan was venturing into territory then unusual on the ballet stage. The Burrow foreshadowed such later works as Valley of Shadows, Playground and Different Drummer. Arnold Haskell’s programme note for the premiere read:

“There are many today who live in hiding, sealed off in some small room. Such a room is a small world in which life burns more intensely; the flickering of a light bulb may bring despair. The ballet introduces us to such a world; there is the woman who is close to breaking point; the man who is an outcast – even the victims of intolerance are intolerant – the over-cheerful man, whose humour is a bludgeon; the child unconscious of fear but quick to seize the mood; and the lover who can never be alone. A knock on the door and their world is shattered.”

There are some twenty dancers on stage throughout. Nicholas Georgiadis’s claustrophobic set, in browns and buffs, was an attic room with a narrow closed door, which became the focal point as the ballet neared its climax. For his score, MacMillan looked again to Frank Martin whose Petite Symphonie Concertante he had used in Laiderette.

For some reviewers, the concentration of dancers in a confined space was startling and dramatic; others commented that it made for fragmentary choreography and loss of impact. Clive Barnes, writing in Dance and Dancers, praised the performances of Lynn Seymour and Donald Mac Leary as touching, hesitant young lovers (“Seymour showed a charming quality all her own and should prove a distinct acquisition for the Royal Ballet”). Barnes singled out Donald Britton’s Joker as “one of the finest male character performances yet seen in British ballet.” For an audience with recent memories of war and whose younger members had known nothing but the Cold War, The Burrow was powerfully resonant. “Fear is something familiar to MacMillan’s generation”, Barnes continued, “something we instinctively recognise.”

The Times review (unsigned) commented: “Although there is no overt message, it somehow recalls The Green Table, perhaps because both are tracts on war, but though it generates considerable tension through the imaginatively conceived choreography – restricted movements, sudden tutti stampedes, contorted enchainements – it has not in sum the emotional power of that remarkable sermon in dance. Yet it is sufficiently dramatic in its three tableaux to make one glad when it ends.” The Guardian’s review (also unsigned) suggested that “the work does not grow dramatically – when the knock on the door comes, one feel that it might just as well have come much earlier or much later – but its flashes of individual dance are impressive ; and altogether it has speed, tension and an atmosphere of fear”

At the Copenhagen Festival in June 1961, the Royal Danish Ballet danced The Burrow along with Danses Concertantes and Solitaire in a MacMillan programme. “The Danes have skilfully mastered the alien style”, The Guardian noted approvingly, “and it was good to find that this versatile young choreographer is being hailed in Copenhagen as an outstanding creative talent.”

In 1992, Kenneth MacMillan recreated The Burrow for Birmingham Royal Ballet, this time with new designs by Nicholas Georgiadis suggestive of one of today’s cardboard cities of refugees. In important respects the recreation was a new work; the surviving Benesh score was fragmentary and the archive film poorly shot. Judith Mackrell, writing for The Independent, commented:

“Perhaps the most startling effect, which MacMillan hasn't tinkered with, is the way that all 21 dancers remain on stage throughout - fighting for space in Nicholas Georgiadis's dark and cluttered set yet often moving with frantic energy. Complex formal dances are fractured by brief scrappy fights, by a furtively grabbed embrace, by a child playing or by an old man shambling about his own half-crazy business. A single phrase alternates between deft classical steps and skewed, slumped, expressionistic body language. The effect is of torn remnants of civilised behaviour fighting for survival in a hell of fear and disorientation.”

First Performed: 2 January 1958

Company: Royal Ballet Touring Company, The Royal Opera House

Music: Frank Martin

Design: Nicholas Georgiadis

Cast: Anne Heaton, Donald Britton, Edward Miller, Lynn Seymour, Donald MacLeary

The World of Paul Slickey

1959

The World of Paul Slickey

1959

Kenneth MacMillan had been an admirer of John Osborne’s work since he had seen Look Back in Anger in 1956. Years later he wrote to Osborne: “Your play made me see that everything in my world was merely window-dressing.”

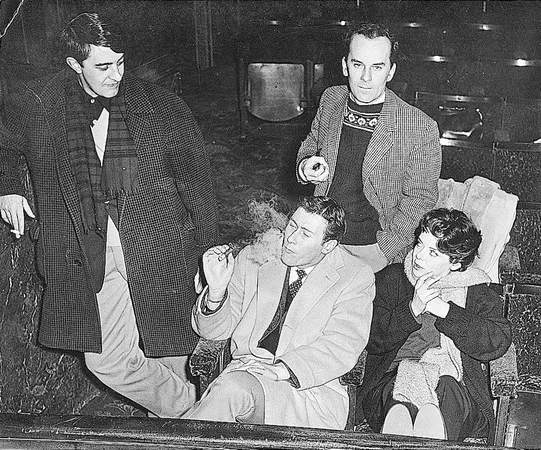

Kenneth MacMillan with John Osborne, Hugh Casson and Jocelyn Rickards

When Osborne was making plans to stage his musical satire, The World of Paul Slickey, he hired MacMillan as choreographer and Hugh Casson as set designer on the advice of Jocelyn Rickards, Slickey’s costume designer. Osborne had met Rickards, his future lover, when she had assisted on the film version of Look Back in Anger. A ballet choreographer working in West End musicals was not new; Frederick Ashton, Antony Tudor and Ninette de Valois had all worked in commercial theatre, and MacMillan’s contemporary, John Cranko, had achieved a smash-hit with his revue Cranks in 1955.

Slickey was intended as a savage jab at London's Fleet Street gossip columnists and at the ruling class, its lead character patently based on The Express’s William Hickey. It was a critical fiasco, not least because of Osborne’s chaotic direction (he had insisted on directing the production). Booing broke out in the stalls half-way through the show (Noel Coward and John Gielgud were among the booers) and afterwards Osborne was chased up the Charing Cross Road by irate theatre-goers. The next day’s headlines were scathing: “The biggest floperoo ever”, “Evening of general embarrassment”, “Sad day for Osborne”. The Times dismissed the piece for its ‘extraordinary dullness’. “Incredibly naive and dull," said the Evening Standard.

The major dance number was the funeral of one Lord Mortlake. For Dancing Times this was “a nightmare ritual taking the form of a rowdy alcoholic rock’n’roll orgy....the cigar-smoking clergyman wears a garment more like a tutu than a surplice.” Its critic, Eric Johns, praised “an excellent cha-cha number which captures the very beat of Fleet Street” along with ‘On Ice’, “a clever satire on smart women journalists, inspired by those absurd attitudes struck by models on the fashion pages of the glossy weeklies.”

But for Philip Hope-Wallace of The Guardian the dance routines were too long and carried “what looks like the date stamp of the Ballets Joos”, while The Observer dismissed them as “mere choreographic exercises” which failed to advance the story.

This was scarcely MacMillan’s fault; Osborne had torn the dances from their intended contexts and staged them as stand-alone set pieces. The World of Paul Slickey closed after a run of six weeks.

Agon

1958

Agon

1958

Agon (1959). Photo: Roger Wood. Image courtesy Royal Opera House Collections (www.rohcollections.org.uk)

MacMillan’s Agon was premiered at Covent Garden eight months after New York City Ballet first danced George Balanchine’s definitive version for which the score had been commissioned. It was one of four settings of Agon performed in Europe that year – the others were by German choreographers – and was MacMillan’s second ballet to a Stravinsky score (the first was Danses Concertantes). In an article for the Royal Opera House’s then house magazine, Covent Garden Books, MacMillan characterised Agon as an off-shoot of Danses Concertantes and a reversion to that style.

Stravinsky’s markings indicated a cast of twelve dancers, who are introduced with a pas de quatre, double pas de quatre and triple pas de quatre. As the ballet unfolds the twelve dancers re-emerge in various permutations. However, MacMillan chose to add two ‘extra’ dancers both to introduce the twelve and to form links during the Preludes and Interludes. His version bore little relationship to the austere modernism of the original. But because Stravinsky had named the ballet’s central sections for sixteenth and seventeenth century dances, the sarabande, the gaillard and the bransle, Nicholas Georgiadis sought for inspiration in that period for his designs. The costumes, sprinkled with harlequin patches, have a flavour of the commedia dell’arte and suggest a troupe of strolling players. The set designs suggested the facade of a house, mysterious cut-out figures watching from a balcony (Peter Williams wondered if they were ‘eternal voyeuses prying on our private lives and passing private censure’). The colour palette was Mediterranean; orange, sunbaked white and contrasting black.

Agon (1959). Photo: Roger Wood. Image courtesy Royal Opera House Collections (www.rohcollections.org.uk)

While there was no scenario, Clive Barnes, writing in Dance and Dancers, asserted that this Agon could be loosely defined as a story-ballet, the scene a bordello, the narrative one about “love in the Waste Land” and about the Fates and their blind indifference to humanity. MacMillan accepted that while the ballet had no narrative element, there “was a certain basis of truth” to the suggestion that the action took place in a brothel.

Nonetheless, the Diaghilev conductor Ernest Ansermet considered MacMillan’s Agon “the first truly abstract ballet he had ever seen”. The first night audience was enthusiastic (there were thirteen curtain calls). Clive Barnes, writing for Dance and Dancers, praised MacMillan for “catching the right weight of dance to support the orchestration”. In The Financial Times, Clement Crisp characterised MacMillan’s vocabulary as “extremely rich, by turns extravagant and declamatory”.

However The Times was unimpressed with the score’s ‘bankruptcy of melodic invention’ and characterised MacMillan as having ‘somehow made bricks without straw, a silk purse out of a sow’s bristles’. Alexander Bland of The Observer wrote of a missed opportunity which nonetheless had ‘some fascinating side-products’. “The choreography is, in fact, full of invention and aptly set to the music. But the economy and simplicity of the score is not reflected on the stage. Instead MacMillan has spread over it a veneer of rather facile coffee-bar mannerism which gives a fatal twist to the proceedings – a twist towards the kind of gimmick mannerism which dates with this year’s waist-line. This attitude is reflected even more strongly in the costumes. I should like to see this interesting work in practice dress.”

MacMillan’s Agon was performed for one season and was danced nineteen times. No Benesh score exists. Although the system had by then been accepted by the Royal Ballet, the company’s first notator did not start work until 1960.

First performance: 20 August 1958

Music: Igor Stravinsky

Design: Nicholas Geordiadis

Cast: Anya Linden, David Blair, Deirdre Dixon, Ronald Hynde

Expresso Bongo

1959

Expresso Bongo

1959

Expresso Bongo was MacMillan’s second foray into musicals (his first was choreographing John Osborne’s disastrous The World of Paul Slickey in 1958). A satire on the music business, Expresso Bongo had begun life as a successful West End musical in 1958. The following year it was made into an even more successful film starring Laurence Harvey and Cliff Richard, becoming one of the ten best-selling films at the box office that year. Its leading character is a sleazy theatrical agent on the lookout for fresh talent to exploit. He discovers a teenage singer named Bert Rudge in a coffee shop, changes his name to Bongo Herbert, and a star is born. Fame, a record deal and the inevitable recriminations follow.

Val Guest, the director, engaged Kenneth MacMillan to choreograph the strip-club dancers who appear in the film. Struggling at Shepperton Studios to get them to dance and sing at the same time, MacMillan complained; “It's the simplest routine. They may have looks, legs and tits, but they have no co-ordination.” Nevertheless for his efforts MacMillan earned more than he would have done in a full year at Covent Garden.