The only clue MacMillan gave to his last ballet is a programme note quoting the Sufi writer Kahlil Gibran: ‘As a single leaf turns not yellow but with the silent knowledge of the whole tree, so the wrongdoer cannot do wrong without the hidden will of you all’.

The Judas Tree is a ballet about betrayal and guilt, individual and communal. MacMillan based it on the iconic biblical story of betrayal, the Judas kiss that resulted in Jesus Christ’s crucifixion. He was also thinking of more recent instances of betrayal, such as the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. Protesting students demanding democratic reforms had been mown down by the Chinese army, in spite of politicians’ assurances that there would be no violence.

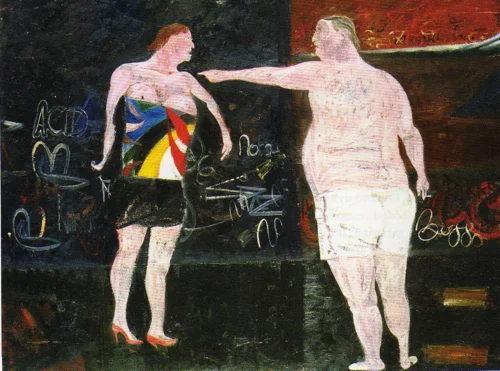

Original painting by Jock McFadyen

MacMillan had discussed his general ideas for the ballet with Brian Elias when he commissioned a 40 minute score in 1989. Elias took his inspiration from research into the myths and scholarly studies about Judas and the Apostles. He passed on his findings to MacMillan, who selected what he wanted from the mass of information Elias had provided when he started work on the choreography in 1991.

Both men were fascinated by the Gnostic Gospels, papyrus fragments discovered in 1945 in Egypt, near the town of Nag Hammadi. They were Coptic translations, made in AD 350-400 and preserved in desert caves, of more ancient manuscripts written in Greek. The writers claimed to reveal stories about Jesus and his disciples that were hidden from ‘the many’ – beliefs that had been denounced as heresy by the early Christian church.

Among the mystical ‘gospels’ was one in the name of Mary Magdalene, who was apparently a favoured disciple, privileged to receive special knowledge. The Nag Hammadi codices also included many scraps of poems by and about women. In one, the soul is described as a woman who was virginal while she was with her Father in heaven but a prostitute when she fell into the world. She was abused by men until she appealed to the Father to restore her to himself. She regained her former purity and was recalled into heaven.

The sole woman in The Judas Tree is called Mary in MacMillan’s and Elias’s notes, though she has no proper name on the cast list. When she wraps her long veil around herself, she resembles the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene in Christian paintings, as well as a veiled Muslim woman. MacMillan intended the ballet’s setting to be a modern one for an archetypal story. He chose as his designer the Scottish painter Jock McFadyen, whose work he had seen in a London gallery. McFadyen’s studio was in East London, close to the area where the Canary Wharf complex was under construction, displacing the former inhabitants. ‘Mary’ in the ballet is scantily dressed like one of the East End women in McFadyen’s paintings, seen against a graffitti-scrawled background.

The title of the ballet is the common name given to a tree that bears purple-red flowers along its branches before the leaves come out. The flowers are supposed to represent drops of Judas’s blood, spilt when he hanged himself in remorse for having betrayed Jesus. In McFadyen’s set for the ballet, the tree is the newly completed Canary Wharf tower. The thirteen men are a gang of construction workers, overseen by the Foreman, who will turn out to be the Judas figure.

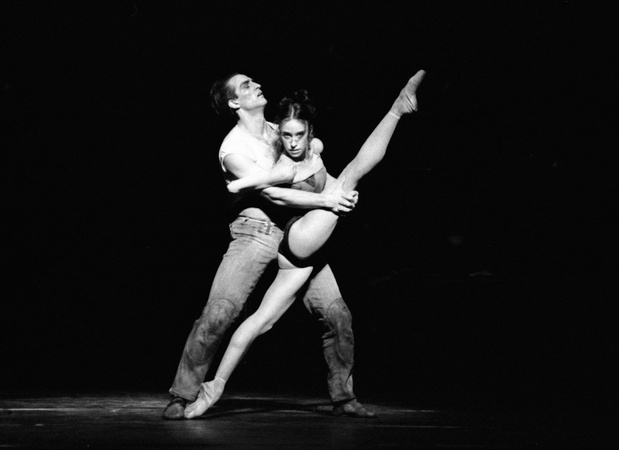

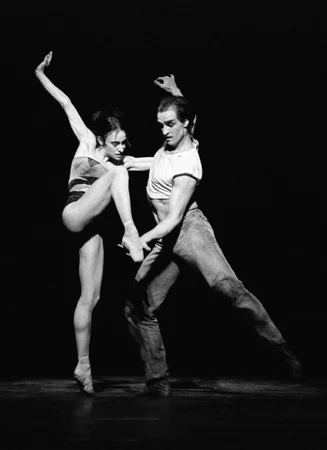

The woman first appears as a mysterious being under a shroud. When she is unveiled by the workmen, her provocative behaviour arouses the Foreman’s jealousy. Her presence sets the men against each other, especially when she seems to favour one, the Jesus figure, over Judas. The Foreman abuses her and then condones her gang rape by the workers. When she points accusingly at him as her betrayer, he breaks her neck. Jesus comes forward to protect her body, only to be grabbed by Judas and brutally kissed – a signal for the gang to lynch him.

Dressed in yellow slickers that make them anonymous, the men descend on Jesus like a pack of animals. They stuff his lifeless body into one of the wrecked cars on the set as a makeshift sepulchre. Judas, aware of the enormity of his guilt, hangs himself from a girder. As his body dangles, the woman walks in, draped in her veil, and stands, head bowed, between him and Jesus. Above them, a light flashes at the tip of the Canary Wharf tower.

For all its horrific violence, the ballet holds out an element of hope. The woman cannot be defiled, broken or killed. She is not a person but an unquenchable force: the soul, the Madonna, perhaps the female side of themselves that men deny at their peril. She alone remains at the end as a witness of their fallibility.

The Judas Tree is open to many interpretations, secular and religious. Its context is contemporary, yet the sacrificial ritual at its core reverberates through time. MacMillan was driven to create controversy even at the end of his life. He had succeeded in commissioning a remarkable contemporary score from Brian Elias and a memorable set of a London landmark from Jock McFadyen. But in its early performances, the ballet was often misunderstood as a degrading exploitation of a woman’s sexuality. Over time, audiences have learnt to approach its meanings less literally.

First performance: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 19 March 1992

Company: The Royal Ballet

Cast: Irek Mukhamedov, Viviana Durante, Michael Nunn, Mark Silver, Luke Heydon

Music: Brian Elias, The Judas Tree (commissioned score)

Design: Jock McFadyen

Benesh notation score: Monica Parker (1992). Working score

Video: DVD (NVC arts), director Ross MacGibbon